Inside My First Bank Run: Zombie Banks and Magic Money

Why Banks Always Explode And What To Do About it

I’m writing this essay the weekend after what was almost a financial apocalypse for Silicon Valley (note: publishing will be delayed because of said apocalypse). That so much drama could have been resolved within 4 days is a sign of the times. This is really two separate essays glued together, but they each draw from each other heavily. The first is an explainer of how and why we navigated our first bank run, along with some brief commentary. The second expands on a way to view banks and our banking system that made some of the decisions from Part I happen quickly.

As an active participant in this particular drama, it was fascinating to watch the absolute conviction with which the commentariat posted their takes online. Gell-Mann Amnesia is often cited, but I think many people forget the very first step in the amnesia:

You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues.

Everyone always focuses on the amnesia part of applying this to other disciplines. Nobody ever disagrees that the state of affairs for one’s own discipline is so bleak.

As time moves on, our understanding of the SVB saga will improve. More sophisticated writers will take the time to understand what happened and then share their thoughts with the rest of us. The amount of conviction expressed on Twitter will unfortunately remain constant, but the complexity of the arguments will increase somewhat over time as the battle-lines are drawn and the professionals have time to build their arguments up.

Such is the meta-process by which we collectively come to interpret historical events. Today it happens on Twitter. A hundred years ago it happened in the papers.

Unsurprisingly this process is absolute dogwater rarely produces much sense, and if you use it to build your model of “how the world works”…good luck. But it is entertaining. And if your verbal intelligence is enough standard deviations above average, it can be very financially rewarding.

Alas, I got an engineering degree so you’re stuck reading my inside perspective on The Bank Run after the event instead of pithy takes live-posted as the bank collapsed. Please forgive the long preamble here, the goal is to dissuade uncharitable people with low patience from reading.

Part I: The Setup

I returned from paternity leave in July, 2022. Inflation was clearly higher than the experts had forecast and rates were hiking fast:

At this point our money was parked exclusively with SVB. Obviously this was not good. The first conversation we had when I got back to work was about making sure we weren’t leaving free money on the table by not taking advantage of the higher interest rate environment.

When I learned what we were getting from our existing SVB account, I was frustrated for exactly the reason twitter poster “EncinitasImposition” noted on Saturday:

“i was a little annoyed it wasn’t happening automatically.”

Me too, buddy. It turns out that even with a business account worth $Xm this stuff doesn’t happen automatically. There are reasonable explanations here, but at the time my personal Vanguard brokerage account was paying me a higher risk-free interest rate on idle funds than our business account and no amount of reasonable explaining stops that from tasting sour.

We didn’t get things formally set up with another banking partner until the end of the year. If SVB had collapsed in December — when the first known criticism of the bank was published — we would have been cutting it very, very close. I’m grateful luck was on our side here.

All this background means that we had an alternate bank available to wire funds to.

The more interesting part was deciding to participate in the bank run on Thursday morning.

My First Bank Run: Why We Moved The Money

We’d been discussing our relationship with SVB in our team’s slack channel on Wednesday (unrelated to any of the above).

On Wednesday night, one of the guys on the team sent a tweet to our channel noting that SVB’s stock was down 30% after hours and linking to their “Strategic Actions” deck:

I saw his message at midnight. Raised my eyebrows and took a quick look at the link. It was full of hard-to-read corporate language. The private equity investment looked suspect (read: because one typically does not call up the sharks and ask for help when things are going well).

I didn’t do anything else. Went to bed with no thought beyond: “that’s not good for them.”

That they were our bank, with $Xm of our money, didn’t fully register.

I woke in the morning to news that their stock was now down 60%! Literally while brushing my teeth I saw some concerns about their solvency.

“People are suggesting your bank might be insolvent” and “your bank’s stock is down 60%” were sufficient to make a decision.

I am occasionally prone to overcorrection of prior mistakes by temperament, and the thought that we could’ve missed our window because I hadn’t fully figured out what their “Strategic Actions” mid-quarter update meant before going to bed definitely occurred to me.

I sent a quick slack message at 8:28am to a team member: “we may need to move our money out today.” He replied: “Uh oh.”

After a quick pricing call with sales for a deal, we got the finance team together and agreed on a simple plan (copied & pasted below):

Action Items:

Set everything in motion to initiate a wire for $Ym

Email [alternate bank] detailing the situation

Email SVB

Send note to board on current plan of action and solicit feedback

Before end of day (5pm Eastern) → move money

Create list of auto debits from SVB

Create list of customers we need to notify

It was now 10am on Thursday.

I updated our CEO, explained the plan, and asked him to reach out to the board.

We heard back from two of three board members almost immediately that the plan sounded great, no need to delay.

At 10:30am we scheduled a wire out of SVB.

There was a bit of a delay approving it on our end as our CEO was in a prospect meeting and I felt that was more important. Around 11:30am we received confirmation from our alternate banking partner the wire had been received.

I pedantically note the times here because there were a few moments we could have moved faster. We didn’t, because I didn’t think it likely that SVB would collapse. I said “2% chance” in the morning as we made our plan and told my wife “maybe 10%” while making a cup of tea. In an email I sent at noon updating folks on how things stood, I wrote “…things will probably resolve themselves with SVB…”

In hindsight, these delays could have cost us dearly in a hypothetical world where wires out were frozen at lunch time.

Regardless of urgency levels, “there’s a 2% chance your bank doesn’t exist tomorrow” is in fact multiple orders of magnitude too high for anyone personally responsible for large sums of cash. People not responsible for such sums have shared many opinions online about the most prudent way to operate in scenarios like this, but the lack of skin in the game makes those opinions somewhat meaningless. At best, only my own job was in jeopardy. At worst, many others’ were at risk.

“There’s a 10% chance the coffeeshop won’t be open” is not a big deal. You should still go get that coffee. If it’s closed you can go elsewhere. If all the coffeeshops are closed, you’ll survive and the walk will still have been a pleasant break.

But “there’s a 2% chance you can’t make payroll”, or “there’s a 2% chance you lose months of company runway” are not risks worth taking. The cost of being wrong is damage to our relationship with SVB. That’s unfortunate and I hope(d) to mitigate it. But relationship damage can be repaired. Evaporated runway cannot.

By 6pm I was eating dinner and talking about the day with my wife. It occurred to me then that we might have made a mistake. I hadn’t revisited my “probability bank collapses” estimation since the morning and hadn’t seen Twitter or the news either. After moving our funds we’d worked on customer comms and searching for a replacement banking partner all day. But given the probability of bank failure seemed low, we’d left 2 months worth of spend with SVB in order to make payroll and some large vendor payments we had coming up (& without someone on the team’s quick thinking it would have been 3 months’ spend!).

Online sentiment by 6pm was much, much worse. SVB’s survival felt 50/50 to me. Moving that chunk of cash to money market funds was small consolation — if the bank exploded, it could be a year before we saw it. If we saw it.

In reality of course, the bank no longer officially existed by the time I was eating dinner and these worries were far too late.

SVB’s end of day balance was negative one billion. Negative one billion dollars means you are now government property.

Now that the whole thing’s been cleaned up by the government, it feels strange to recall the aura of dread and uncertainty that blanketed everyone in Tech from Friday through to Sunday’s announcement. Twitter was full of angry people pointing fingers, but most people actually involved in the crisis were silent. I recorded a short vlog for myself on the Saturday to look back on later —it was a somber and depressing video.

$42 billion withdrawals in a single day is impressive. But SVB had had $326 billion in client funds (split 50/50 deposits vs. off balance sheet funds) on Wednesday. Which means only 13% of funds were withdrawn before the doors closed. The rest was stuck in limbo.

Analyzing The Crisis From Within The Crisis

Our confidence that the funds we left in SVB could support payroll and vendor expenses helped us make the decision to move money out so quickly. But in an alternate world where the FDIC hadn’t announced on Sunday that they would print as much money as required take action to secure depositors…my failure to check market sentiment and re-evaluate the risk could have been an expensive lesson.

At 7pm I started work on some “Market Update” slides for the rest of the company. This was the first time I tried to figure out what had actually happened and only 9 hours after it had all kicked off. We have a massive 100 reply thread trying to figure it out in our team's slack channel.

At this point I’d read SVB’s “Strategic Update” deck and translated the first slide from Corporate Language to Conrad:

The thing that we kept coming back to: why did they have to sell their securities now. Why sell everything today?

Why do a Wednesday night announcement? “Special mid-quarter update” is not a good thing. Why now? Why couldn’t this be managed slowly and responsibly over a longer period of time? Why was their hand forced?

This was the best answer I could come up with on Thursday night:

“Not enough securities maturing to pay for outflows” is some Corporate Language of my own. In layman’s terms…they don’t have the money. And they expect people to ask for it. Soon.

In isolation, there are other potential ways to read this slide. But the surrounding quotes around this chart accused startups of burning too much cash and investors of not deploying enough capital investing in new startups. It doesn’t take ChatGPT5 to read between the lines here. SVB was expecting to be unable to meet depositor withdrawal requests.

If there’s an alternate way to read slide 16 in their “strategic” announcement deck, I’d love to hear it. I imagine SVB would have been ok in Q2, but the question the deck leaves me with is “how many quarters of negative $20b in client funds can your bank sustain?”

This was very different from the news takes I’d been able to find online. The most popular positions at the time were:

I’m sure my own late-night post-hoc “sense making” attempts are also flawed, and certainly a single slide and 2.5 paragraphs doesn’t do justice to the multi-causal shitshow that happened last week. But I share this attempt at understanding because it’s more interesting to consider the analysis we had within the crisis than the stuff we can come up with now, weeks later. I don’t claim the above explanation is authoritative — it’s just my own best attempt at understanding a bank run a few hours after participating in it.

A decision had to be made in the moment and then explained to the team. The professionals had not released their verdict by Thursday evening.

I think there’s a bigger personal lesson here too: for any sufficiently severe crisis, a decision will be required before perfect information is acquired.

Part II: Tough Decisions Are Easiest When They Align With Your Worldview

Pulling the trigger on short notice before the social consensus has fully developed can be tough. A lot of the media hubbub around this bank run has pointed the finger at VCs for orchestrating the crisis. In contrast, I think this is exactly the sort of situation that a VC can be ultra helpful to a company. An outside voice granting license to make a brash decision can help companies who would otherwise dilly-dally their way into a bank run.

Regardless of your opinion around herd-like behavior, once a bank run is underway you only have two options: get your money out or don’t (some lucky folks also have a third: pay homage to the Fed). People who get this, get it immediately. People who don’t, lose (money).

If you’d restricted the communication of every VC with their portfolio companies for all of Thursday, you probably could have reduced SVB’s withdrawals somewhat. The bank may have been able to shuffle money around and scrape through the crisis without triggering its own dissolution by the government.

But if you had to assign probabilities there…is it 100% likely that the bank makes it? I doubt it (update: Credit Suisse just had to deal with $10b in customer withdrawals per day for a week before its fire sale— hardly a compelling alternative).

Founders may call their boards first. But then they call each other. VCs accelerate how fast news moves down the grapevine, but the news moves regardless. I found time on Thursday to call a couple friends on the phone after getting our money out of SVB. I’m sure others did the same.

The world is chaotic and uncertain. The only thing I feel confident in here is that VCs were not the first to notice SVB’s precarious position, nor the first to comment on it online, nor the first to read their Wednesday announcement as a warning sign. Did they accelerate things? Yes. Was that acceleration measured in hours, days, or weeks? Unclear. My guess is days.

Media commentators have & will continue to fixate on VCs because they’re a functional outgroup for an increasingly tech-hostile press (“wealthy cabal of elite financiers” is an easy slam dunk and always has been). They will not focus on the December 2022 Seeking Alpha blogpost suggesting SVB was insolvent or Byrne Hobart’s (expensive!) February newsletter post outlining the same. They will not focus on SVB’s poor decision-making — both its questionable macro decision-making (why buy $80B of Mortgage Backed Securities? why wait until rates went to 4.5% to try and address the problems?) and its micro decision-making within the crisis (you can lambast the Tech scene for many things, but these people expect clear & decisive executive communication and assume its absence is evidence of incompetence — in this case, that assumption seems prudent).

In my case, I have some personal views on our magical banking system that influenced our decision making. If you’ve read enough of my writing, they won’t be surprising to you. Net net, they sum to the idea that banking collapses are a near-certainty in adverse financial situations and that navigating them responsibly requires adopting a zero-sum mindset. I try not to talk too explicitly here, because eventually you end up talking policy and I would never do that to my dear readers. But if you want the relevant snippets, these ones are close enough:

Financialism: You Don’t Need Surpluses If You Can Trade With The Future:

Note: magic isn’t real. Magic that lets you “snatch” value from the future should be read with a certain tone of voice. Note that the magical calculations described in this quote are exactly the kind that SVB got wrong.

The Germany Shock: The Largest Economy Nobody Understands:

aka tightly interconnected systems are beautiful marvelous wonderful systems of positive-sum value creation…and when they unravel they will take your job, your house, your community, and your city with them.

(this is bad)

(tech is a tightly interconnected system)

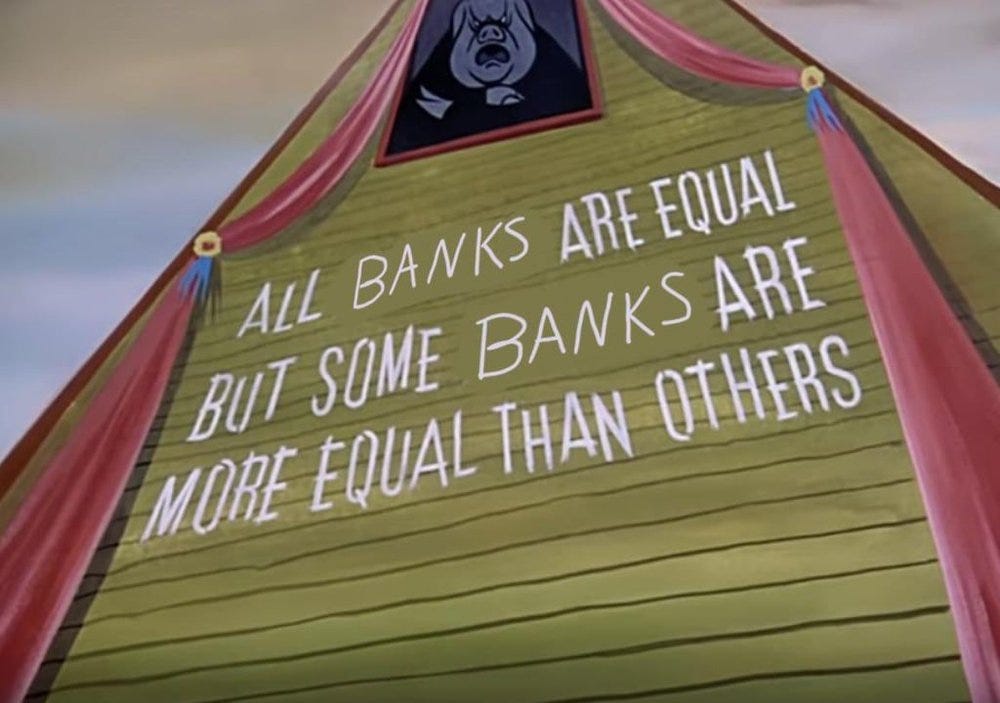

Unequal Growth: The Zero-Sum Games You Don’t See Essay:

Read: ”even in a crisis, somebody wins.”

Subtext: make sure it’s you.

Moloch Is Our God: AI, Mankind, and Moloch Walk Into A Bar — Only Two May Leave:

Translation: ”when in an existential situation, default to choosing Strategic Dominance”

(note: bank runs are existential)

Exploding Zombie Banks

I’ve been reading Patrick McKenzie for over a decade now and his long-form writeup of this whole event is superb. It was on HackerNews all day today. You should read it.

But if I might excerpt one part of it to make a personal point and highlight the way I see things:

In my mind, this is directly tied to my essay on existential competition Moloch, linked above:

Patrick’s quote — “Society depends on this existing. The alternative is a much poorer world.” — is a true and accurate statement.

That society depends on this banking model is a fact. That the alternative is a poorer world is a fact.

Such facts should be treated with respect. Like a bomb.

And so Patrick continues in his summary of SVB:

“The dominant way people bank sometimes explodes.”

This is said plainly and simply and you can’t contest it and you should respect Patrick for being sophisticated enough to understand the system and honest enough to say it out load. It’s a core feature. It’s such a competitive advantage that any institution not operating this way will be consumed by one that is.

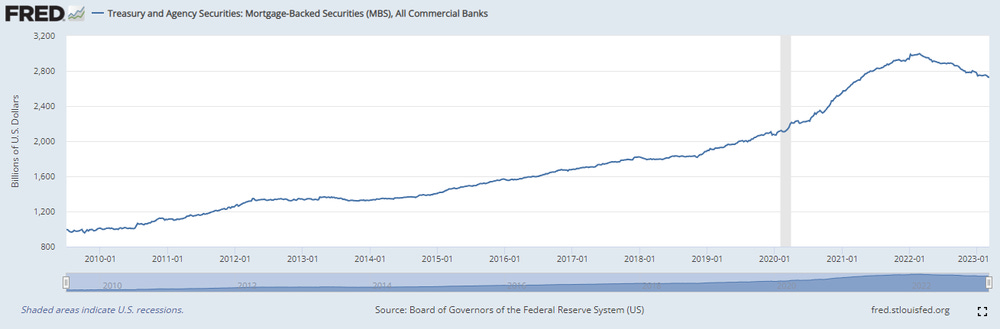

Note the follow up call out of “securitizing mortgages” (Mortgage Backed Securities) and selling them to pension funds. Note also that SVB bought $80 billion of these things (thanks to my teammate for digging this up in their 10K). And note that MBS have a particularly strong exposure to the types of phenomenon that cause banks to “sometimes explode” due to their insanely long duration and correlation with other things going splat.

Earlier in the piece, Patrick calls out that people will overly-fixate on his callout of Mortgage Backed Securities as being involved in this event.

But contra- this position, I think you are probably wise to minimize exposure to institutions dealing in or selling you these things if you are personally responsible for $Xm. Unless that institution is significantly more sophisticated than average among its peerset at navigating this specific subset of finance arcana — and I regret to say that “#16 ranked bank specializing in technology clients” is not sufficient here — assume that they did the magic calculations wrong. Assume they missed something. Assume they have an albatross round their neck of assets they barely understand and most certainly can’t move in a crisis.

Assume the bomb is ticking.

And with a vivid picture like that of a bank walking towards you, ticking bomb strapped to its chest, consider that some banks are very alive, very alert, and highly motivated to defuse the bomb. Others…are less used to taking bold independent action. Others are more like zombies, shuffling along, step by step, tick tock, tick tock.

If this position seems unfair, I’m happy to hear arguments on it. I don’t mean to throw shade on anyone here — obviously I deem myself incapable of navigating these calculations as well. But I’ll steer clear of anyone selling me extra bps in exchange for long-duration fixed-rate asset exposure. The bonus yield in the short-term isn’t worth the added existential risk to me and I’d prefer to spend my spare brain cycles building.

You don’t need to be the smartest guy in the room to reduce your exposure to this stuff.

You do if you want to make money on it.

The zombies just go boom.

Time Is Money, Friend

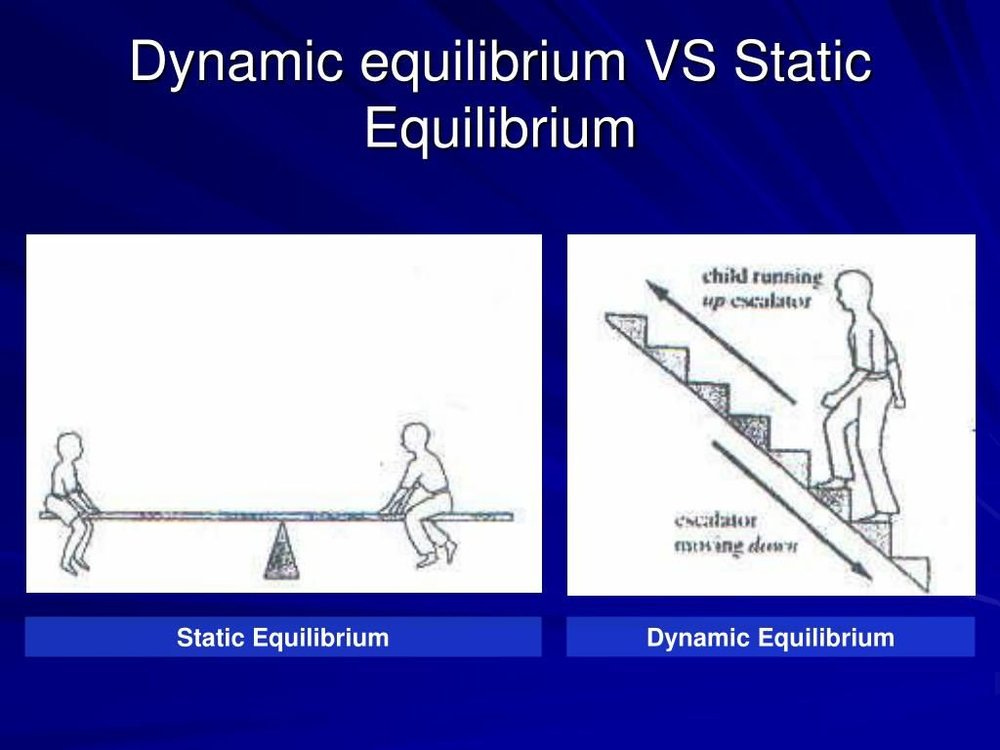

In a short vlog over Christmas I tried to articulate something that’s been on my mind lately: the importance of understanding the role Time plays in any given phenomenon. It’s a mouthful, I know. Some people are quite good at it. Others not so much. But most things in life don’t come with an annotation that explains how the behavior within the system unfolds over time — and how perturbations to the static system impact that unfolding going forward.

However, if the only functioning model of reality you have is a static one, you’re going to get hurt:

Standard undergraduate Mechanical Engineering starts kids off with a 101 course dealing with Statics, because adding time to any system completely fucks with puts major strain on your ability to model it. Dynamic systems (1) come later after you’ve shored up your math skills. But modern finance is built on the time-based Wizardry described in my Financialism essay: which, translated, means it’s built on taking dynamic systems and modeling them as static ones.[2]

If you have an engineering degree and fully understand the implications of that sentence, you might begin to appreciate why “your bank might explode” has non-zero probability at any time — and why the overlap of that sentence with a 60% drop in the bank’s stock is entirely sufficient to move millions of dollars.

If you don’t quite understand the sentence, it means that a bank can appear to be “solvent” — that is, Assets = Liabilities + Equity on paper — and yet also “not have the money.” Some high-follower VCs were tweeting mid-bank run that they believed SVB’s CEO when he said the bank was solvent. This was a reasonable statement, and we all should believe SVB’s CEO (probably).

But note this definition of “solvent” does not translate to “we have the money.” Nor even to “we will shortly have the money.” In fact it could quite plausibly translate to “we will not have the money until after you are retired and your professional career has ended.” This is the magical “role that time plays” in our banking system.

Say a bank owes you $100 today. It also expects to receive $100 in 30 years time, broken up into a series of small mortgage payments and spread out over that 30 years (plus interest). From an accounting perspective, these elements cancel each other out. If you have studied Mechanical or Electrical engineering in any capacity, I invite you to imagine a suitable analogy here for a dynamic system that receives inputs and has equivalent outputs, but no way to fully account for the timing of either.

You might laugh, but bear in mind that the analogy you come up with supports the entire Anglo-American banking system and by proxy…the entire world. And has done for hundreds of years.

There are many ways to contort logic and explain this. But, legally and ethically, the bank owes you $100. Today. Immediately. As soon as you ask for it. Also, they do not have the money. They are in the business of convincing you not to come ask for it. This is a remarkable business. In SVB’s case, they had tied a huge portion of their tech company clients’ funds up for 30 years. This is particularly interesting given what most people know about the burn-raise-burn pattern of tech company cashflow management.

“Particularly interesting” is another way to say “tick, tock, tick tock.”

If this line of thinking seems too fringe or too preposterous or too engineering-brained and you worry I’m suggesting an unreasonable critique of things, have no fear, you can hear the same thing from ex-secretary of the treasury, ex-director of the National Economic Council, ex-president of Harvard, ex-hedge fund manager, Larry Summers:

There’s no more fitting voice.

And before you get the wrong idea and think that any of this is bad or that I’m in any way opposed to this glorious show and want to tear the whole thing down, remember that Patrick McKenzie was entirely correct when I quoted him above:

Society depends on this mismatch existing. It must exist somewhere. The alternative is a much poorer and riskier world…

The inherent splatification of the banks is a feature, not a bug.

We are all muggles. The banks are the wizards.

Ideally the wizards are good at their jobs.

Ideally they do not get the calculations wrong.

Because it turns out that most of us are content to lend our money to banks and have them engage in magic. Our continued collective belief in the fiction is necessary for it all to keep working. So long as they maintain our collective confidence in them, all is well. The “contagion” that scares the Fed & the government is a very real concern: no bank in the world could handle the sustained withdrawal volume SVB had to deal with as a percent of deposits.

If there ever had been such a bank, it was put out of business a long time ago. Moloch sends his regards. Existential competition is a bitch.

But as a depositor — meaning as someone the bank owes money to — your natural attitude to the wizards is not unlike that of a Hollywood mob boss. When the underling who owes you money comes on bended knee and says, “sorry, I don’t have it right now, but I can get it for you tomorrow” then you’ve got a good movie. If he says “next week” then you’ve got an even better movie.

If he says “perhaps not until the Fed cuts rates back to zero” then the movie script gets axed. No amount of “think of the bigger picture” can save that underling.

The audience would never respect the boss.

How To Resurrect A Zombie Bank: Go Brrrrr, Then Grow

If you’ve read enough of my writing, they won’t be surprising to you. Net net, they sum to the idea that banking collapses are a near-certainty in adverse financial situations

This lens from earlier is useful: it says that bank failures are usually a sign of pressure elsewhere in the system.

After all, if folks believed the bank was good for the money, they (probably) wouldn’t bother to try and pull their funds out. The lack of confidence sparks the fire.

In 2008 it turned out that a bunch of people banks had lent money to were, in fact, not good for it (dramatized in The Big Short by a stripper with five mortgages). Also, they gave these people a lot of money. My personal thesis is that this was just the latest act in a very long story of “chasing growth that wasn’t there” that you can plausibly draw all the way back to 1971, with a straight line through every crisis, each one driven in its own way by the search for productive wealth generation.

SVB’s collapse does not appear to be part of that narrative arc. The adverse financial situation that did them in appears to be a combination of locking too much of their cash up in long-duration securities, having a customer base with high short-term cash needs, and rising interest rates in response to covid-flation tanking the value of their loans and destroying their ability to meet depositor withdrawal requests.

Ultimately, there’s only one way to save a bank in the short-term: print money.

If you’re a highly skilled wizard, you can sort of print this money semi-fictitiously, whereby everyone thinks it exists but nobody tries to do anything with it, letting the bank continue operating as if it had cash in the vault and…one hopes…eventually allowing the bank’s long-term profitable actions to return enough capital that it can reorganize its finances without needing to sell assets at too steep of a loss (& thereby put it even deeper into the hole).

Our chief wizards have executed this a number of times. It can be done.

This level of skill is not taught many places because, as you might imagine, it’s ripe for abuse and tends to spark intense populist outrage. If your neighbor tried to do this for his personal account, he’d be arrested. Listen to Sam Bankman-Fried explain how new crypto tokens create value for an example of said arrest (ctrl-f for “ponzi” in that link & ask why FTX depositors were not made whole). Also most people, even journeyman wizards, lack the necessary skill to pull this off.

In the long-term, the only way to save the banks is to generate growth. Anytime (expected) growth fails to materialize, banks will go boom. Their model assumes a steady stream of payments comes in from their book of assets. Turn off the stream, turn off the bank.

Raising interest rates means that the amount of money we expect to get just skyrocketed. Expectations skyrocketing means any bank who can’t be agile enough to keep up is hearing “tick, tock, tick tock,” and praying that Jerome Powell blinks when it comes to raising rates further.

Somebody has to create wealth. If not, a lot more banks are going to go boom.

If we can create wealth, then one way or another, directly or indirectly, through corporate loan repayments or mortgages, that wealth will find its way back to the banks:

aka “Banks are the vehicle through which Macroeconomic policy is delivered to the people.”

Not discussed in that essay was what happens when the banks blow up while trying to deliver said policy.

Given all of the above as a backdrop, it’s hardly a surprise we moved our money out of SVB pretty quickly.

Given $42 billion was moved in a few hours, at least some parts of my worldview are shared by others.

And with that as the backdrop — with anyone responsible for managing a big pool of capital running these exact same calculations and feeling the exact same apprehension about these banks’ ability to weather the storm of 4.5% interest rates — is it any wonder our government moved so quickly to backstop the system?

Banks seem strong until they don’t. To quote a wise man: “up until they lose the game, they’re winning.”

Call it a bailout if you like. Personally I think that description is apt. The types offended by it are just trying to avoid confronting ugliness head on, but I think it best not to shy away from the necessary evils we are forced into. Shareholders got obliterated, yes. God bless the free market. But the very existence of these banks is contingent on an infinite money printer sitting secretly on their balance sheets. SVB’s team is still going to the office, their website still works, you can ACH money in and wire money out, and they are enticing depositors back with “fully FDIC insured” promises. Our 2 months of runway that I worried about costing us by not checking back in on the market before close of business? Wired out 4 days after the bank run.

Some people talk about how normal this is, how it’s a sign the FDIC is good at their job, they’ve done this before, easy as pie, etc.

But consider how magical it is. “Capital holders get wiped out but business continues as normal, the name on the company stays the same, everyone continues to get paid, literally nothing changes except some execs get terminated.” Lenin would almost be proud.

Run the calculus from the capital holder’s perspective and the only sensible place to move your money is a bank that’s already received a government-approved secret money printer on its balance sheet. Call it Too Big To Fail. Call it Systemic Risk. Call it Contagion. Call it a bailout.

Call it what you want: the evil was already injected into the system years ago. Hundreds of years ago. All we can do now is try to keep it operating.

If it is known that the Bank of England is freely advancing on what in ordinary times is reckoned a good security—on what is then commonly pledged and easily convertible—the alarm of the solvent merchants and bankers will be stayed. But if securities, really good and usually convertible, are refused by the Bank, the alarm will not abate, the other loans made will fail in obtaining their end, and the panic will become worse and worse.

— 150 year old cornerstone of modern finance. Go read the link to learn that the advice for dealing with a crisis like this in the year 1873 was to spin up the money printer while raising interest rates. Place your bets on what the Fed decides to do at their next meeting to discuss further interest rates hikes (note: editing this thing took too long, sorry).

That depositors were the ones bailed out and middle-class bank employees get to keep their jobs doesn’t change the nature of the evil. Only the money printer could save these people.

What Happens Next?

The question on everybody’s mind is: what happens next? The most important question in all contexts.

Since I wrote the first draft of this essay, another bank has gone splat.

Will that be all? I hope so. The European Central Banks did some infinite-money guarantees of their own. Of course they did: there’s only one way to save a bank in the short-term.

That said, the primary case for “no further banking crisis” is that everyone in the market believes Jerome Powell & Janet Yellen will print infinite money to defend any bank. When pressed by some politician after SVB exploded, Yellen stressed that said infinite money would only be handed out if:

…a bank only gets that treatment if a supermajority of the FDIC board, a supermajority of the Fed board, and I in consultation with the President determine that the failure to protect uninsured depositors would create systemic risk and significant economic and financial consequences…

the whole segment is worth a listen to. I think Yellen’s position is maximally defensible from the position of trying to limit government involvement and reduce the moral hazard. But. The statement is quite clear. Not all banks will be covered.

Do you believe your bank is safe? Does a supermajority of FDIC and Fed boards, plus Yellen and the President, believe your bank presents a systemic risk?

You need both of those statements to be “yes” — a single “no” means: move your money.

I’m not one for predictions. We’ll see how it plays out. Most potential crises do not develop. If you trust the Fed to be good at their jobs then things should be fine — they are trying to play the delicate game of limiting moral hazard & explicit bailouts with just a few well-placed strategic money-printers on balance sheets…all without causing too much of a political headache. To quote a teammate: “they’re playing hot potato with banks.”

It’s a delicate game. But eventually the potato should cool off.

Mortgage Backed Fictions: Your Mortgage Is A State Product

The last tidbit I’ll add to this topic brings us back to Mortgage Backed Securities and this wonderful article published directly by the Federal Reserve of New York in 2010:

Most mortgages in the US are fixed rate. This is a historical and geographic abnormality. I don’t even think you CAN get a 30 year fixed rate mortgage in the UK. It is the American dream, reified by Fannie Mae and obscure capital ratio rules. It is a direct product of government agencies, and the banks that evaluate, package, and sell them are — in those brief moments — operating as an arm of the state.

It’s uncouth to say this so strongly. In polite company we put distance and metaphors in the way of these things lest we seem unamerican. But you have to internalize this in order to understand why the bankers get the bailouts…and why it is that your 30-year Fixed Rate Mortgage exists.

This abnormality means that when the Fed changes interest rates, that magical stream of payments banks collect from home “owners” doesn’t move whatsoever.

Using a simple econometric model, we find that the low ARM share is largely consistent with long-run historical patterns in household mortgage choice—namely, that households tend to prefer fixed-rate mortgages when long-term interest rates are low relative to recent short-term rates.

So as rates come down, people move to fixed-rate mortgages. It makes sense. People aren’t dumb:

Look at the blue line: up until 2008, 20-50% of all mortgages were Adjustable Rate!

Since this chart was made, we’ve had Zero Interest Rate Policy run for a decade, plus an explosion of bonus liquidity during covid.

So if you swap the camera to a post-2008 view (top-most chart below):

The top chart says ~95% of post-covid mortgages were fixed-rate.

The bottom chart says the banks that sold those mortgages are getting 2% on them for the next 30 years.

And then this chart below says we sold about a trillion dollars worth of those things:

Every single dollar represented in the post-covid spike on this chart pays the bank negative 1-2% in opportunity cost right now. You can “mark to market” and talk about the value of unrealized gains and losses all you want, but the bank’s plan is to hold these things to maturity. And that now means 30 years of losing 2% against the risk free rate.

Banks are in the business of making money. Negative 2% against the risk-free rate is not a sustainable business. If you over-indexed on this shit…tick tock. I hope you’re on good terms with Yellen (for a printer) or Jpow (to cut rates).

Some folks, most notably the All-In Podcast hosts, have commented that Tech companies were going to get crushed by valuation contractions in a 4.5% interest rate environment, that their burn now needs to be managed responsibly because another round of fundraising may not be forthcoming, and that the hurdle rate to deliver investors the returns they need has now been jacked up. These are fair comments.

Tech companies that get it wrong will sputter along to their graves. I’ve been thinking of these companies as “zombies” for months now.

But valuation contraction for pre-IPO companies is an adjustment to paper gains. Company operations can be made more efficient on short time horizons. The hurdle rate determines access to future funding, not current operations.

In sum: none of these factors present a material and immediate drain on the company’s business. The zombie tech companies can shuffle along for some time.

Zombie Banks are not so lucky.

As a friend noted on Twitter, this fiasco is not entirely the banks’ fault. I mentioned capital ratio requirements earlier…it turns out the government set up capital requirements and incentives to push banks into purchasing these things:

Aka: the government says a bank has to keep a ton of cash in its vault if it wants to make loans or buy securities.

Unless it buys Mortgage Backed Securities issued or guaranteed by a government agency. Then? There are no requirements.

Because of course there aren’t. This is a key pillar of state policy.

I focus on Mortgage Backed Securities because their name conjures demons in the dark and the multi-trillion-dollar scale of these long-duration government-securitized assets is so terrifying. But any bank that owns bonds paying them less-than-4.5% and also owes depositors their money back whenever they ask for it…is in a rather exciting position.

I hope this is not many banks. Probably, it isn’t. Probably, things will be fine.

I once wrote a whole essay about how people over-attribute agency to central bankers, who are mostly just reacting to external circumstances with a limited toolset. I stand by that essay. It’s true 95% of the time.

At present, I think we live in the 5%.

Enjoy the moment.

Don’t blink.

Notes

[0] My thinking here is simple: given that rate hikes pushed us to drive a similar gaping hole into SVB’s accounts…and given it was precipitated by the rates they were offering us…and given their own strategic packet says they were only getting 1.79% themselves while the Fed is printing 4%+…well. One might imagine the cash outflows SVB chalked up as “startups burning too much cash” may have been at least partially tied to startups seeking more favorable rates for their idle cash than SVB could afford to give them.

If SVB gave every depositor 4.5%…while locked into getting 1.79% themselves on long-term bonds they bought during ZIRP…they’d go out of business rather quickly, no?

[1] I am in fact visible in the audience of this video, struggling to understand. I’ll buy you a coffee in person sometime if you spot me :)

[2] Some finance nerds may object that the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Myron Scholes & Robert Merton for developing the Black-Scholes model of parabolic partial differential equations that quite explicitly models the dynamic behavior of financial markets containing derivatives. While no Balance Sheet incorporates this stuff in a way that would meaningfully impact the duration mismatch problem, it’s still worth a call out.

The finance nerd within myself would also helpfully add that both Scholes & Merton were founding principals and board members of one of the most spectacular hedge fund explosions of all time. Shoutout to Long-Term Capital Management and its 1998 $3.6 billion bail out (that’s nearly $7b today!).

The engineer in me would add that this is sort of like if Bernoulli had been chief engineer on the Titanic, or if Newton had overseen the development & launch of the Challenger space shuttle. Only those disasters were not directly downstream of the theories of either Bernoulli or Euler or Newton so maybe it’s somehow worse than that.