Book Review: Discourses on Livy, Part I

Rehabilitating Machiavelli

Imagine you’re an intellectual who lives and works in close proximity to your society’s elite. Imagine that your studies of history and politics have inspired a deep love of social liberty and republicanism:

…a form of government in which "supreme power is held by the people and their elected representatives". In republics, the country is considered a "public matter", not the private concern or property of the rulers.

And crucially, imagine that the society all around you exists within the rotten carcass of what was formerly the greatest Republic ever known. Imagine there has been a complete and total decay of moral and civic virtues among the citizenry, only surpassed by an even worse decay in the quality of your political leaders.

You must watch as states around you are invaded because their civic leadership is incompetent, and your own government initiates wars on its neighbours that result in the literal shrinking of your state’s borders and the metaphorical shrinking of its treasury. Violence, poverty, inequality, corruption, sickness, and oppression are everywhere, and the thought of restoring the once glorious Republic seems hopeless.

The future looks bleak, and the most depressing thing is: it’s all self-inflicted.

I am of course describing Italy, circa 1500.

And if you can contextualize the dates and writings of one (in)famous scholar of the times…

…to the events that surrounded him, it is a wonder any rehabilitation is necessary at all:

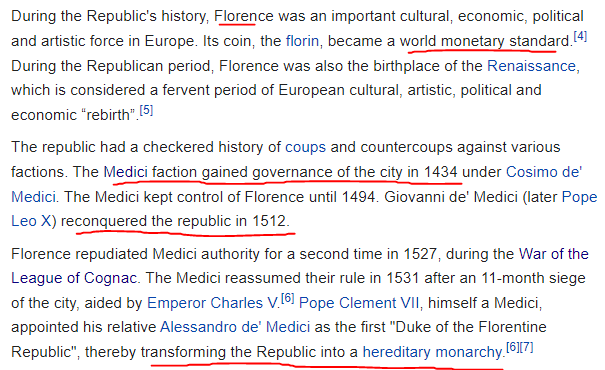

Our protagonist — Machiavelli — was born 35 years after the Medici family had began to grasp power. He lived through the death throes of the Republic and actively conspired to restore it. When the Medici “reconquered the republic in 1512”, per the underlined section above, they sent him into exile and ended his political career.

What a man’s friends say about him is an indication of his character. But what a man’s enemies say about him is often a stronger one. To be condemned, tortured, and rendered unemployable — dare I say properly “cancelled”? — by the monarchy that overthrew the republic…what more needs to be said?

That Machiavelli is best known for his sycophantic book gifted to an aspiring tyrant, complete with a plea to look after his own hide and please not torture him more, instead of the collection of his own pro-republicanism, pro-liberty beliefs dedicated to the friends who forced him to write it, friends who do not even merit their own wikipedia pages, is the ultimate ironic tragedy.

Fate laughs at us all.

The Book Itself: Asking Readers To Do The Work

A fair warning to readers: the book you read will be a modern translation of a work written in the 1500s, that was itself an analysis of another book finished in the year 9BC, accompanied by reflections and juxtapositions between the ancient events detailed by Livy and current affairs — where “current” means circa 1400-1500AD.

But you are now 500+ years removed from those “current” affairs, and 2,000+ years removed from the ancient ones.

Machiavelli lays out the relevant stories from ancient Rome in reasonable detail, while presenting “current” affairs analogies with just a quick reference to a name and a place. 500 years on, the political intricacies of Florentine state-building will likely be completely unfamiliar to any modern reader.

So as a reader you’re trying to construct a functioning mental model of the Roman republic as described by Livy, as then described by Machiavelli, in addition to a functioning mental model of early-Renaissance Italy, as half-described by Machiavelli, and then compare both of those models to your current model of the present and recent past.

I find this quite fun. But I would not say it is easy.

Book One: Internal Affairs

Machiavelli begins by outlining his belief that all governments follow a rhyming character arc that goes round and round in similar circles. This is the longest single quote I’ll make from the book, but I’ll let him describe it in his own words:

A Framework for Unavoidable Regime Change

Chapter 2: How many kinds of republics there are, and what kind the Roman republic was

The heirs immediately began to degenerate from their ancestors, and abandoning acts of special worth, they thought princes had nothing to do but surpass others in luxury and lasciviousness and all other forms of licentiousness. The princes then became afraid on account of the growing hatred among the people, and quickly passed from fear to harmful acts. Tyranny immediately arose.

Subsequently, this gave rise to the beginning of the collapse and the conspiracies and plots against princes, executed not by those who were either timid or weak but by those who surpassed others in generosity, greatness of soul, wealth, and nobility; such men as these could not endure the dishonorable life of such a prince.

The masses, following the authority of these powerful men, took up arms against the prince, and once he had been eliminated, obeyed them as their liberators. And since these men hated the very idea of a single leader, they constituted a government among themselves.

In the beginning, mindful of past tyranny, they governed themselves according to the laws they had instituted, subordinating their own interests to the common good, and with the greatest care they managed and maintained both their private and public affairs.

This administration later passed to their sons, who did not understand the changeability of fortune since they had never experienced evil, and unwilling to remain content with civic equality, they turned to avarice, ambition, and the unlawful seizure of women, causing a government of aristocrats to become a government of the few, without regard for civic bonds of any kind.

In a brief time what happened to the tyrant happened to them, because, disgusted by this system of government, the multitude became the instrument of anyone who designed any kind of plan to attack these rulers, and someone thus soon rose up, who, with the aid of the multitude, destroyed them.

Furthermore, since the memory of the prince and the injuries he inflicted was still fresh, after having destroyed the government of the few and unwilling to reestablish that of a prince, the people turned to democratic government, and they organized it in such a way that neither the few powerful men nor a single prince would ever have any authority whatsoever.

Since all governments receive some respect in the beginning, this democratic government was maintained for a while but not for long, at the most until the generation that had founded it passed away, for it immediately fell into a state of undisciplined liberty, where neither private citizens nor public officials were feared. As a result, with each person living according to his own wishes, a thousand injuries were inflicted every day, so that, forced by necessity or by the suggestion of some good man, in order to flee such permissiveness they returned again to the principality, and from that, step by step, they returned towards a state of undisciplined liberty in the ways and for the reasons given.

And this is the cycle through which all states that have governed themselves or that now govern themselves pass, but rarely do they return to the same forms of government, because almost no republic can be so full of life that it may pass through these mutations many times and remain standing.

It is possible to distinguish Machiavelli’s point here from Fukuyama’s argument in The End of History, and I think arguing the merits of each is a worthy cause, but I’ll pay for the round if you can still do it after drinking a single alcoholic beverage.

Conflict Is A Sign of Healthy Politics

Chapter 4: How the Division Between the Plebeians and the Roman Senate Made That Republic Free and Powerful

Those who condemn the disturbances between the nobles and the plebeians condemn those very things that were the primary cause of Roman liberty. They give more consideration to the noises and cries arising from such disturbances than to the good effects they produced; and they do not consider that in every republic there are two different tendencies, that of the people and of the upper class, and that all of the laws which are passed in favour of liberty are born from the rift between the two, as can easily be seen from what happened in Rome…

This is very much a core part of Machiavelli’s worldview, and comes up in different flavours throughout the book: the idea that it is strife and struggle and turmoil and compromise that keeps a society in balance and alive. Things which his contemporary intellectuals read as signs of trouble are read by Machiavelli as evidence that one side has not succeeded in oppressing the other, and therefore that liberty is alive.

Put another way: the interests of different layers of society will always come into conflict — the absence of visible conflict in a society is therefore a sign of sickness, not health.

It’s the silence you want to watch out for.

A Chief Executive’s Only Path To Safety Is Through The Masses

Chapter 6: Whether in Rome It Was Possible to Organize a Government that Could Do Away with the Enmities Between the People and the Senate

Sparta, as I said, was governed by a king and a senate of limited size. It was able to sustain itself for such a long time [800 years] because it had few inhabitants and access to participation had been taken away from those who came there to live, and once the laws of Lycurgus were adopted to good effect, the Spartans were able to live in unity over a long period of time.

With his laws, Lycurgus created in Sparta greater equality of property and less equality of rank, so that there was an equality of poverty there, and the plebeians were less ambitious since the high ranks of the city, extended to few citizens, were denied to them; nor did the nobles ever give the plebeians any desire to obtain these ranks by mistreating them.

This was due to the Spartan kings, who, being set up in that principality and placed in the midst of that nobility, had no better way to secure their office than to protect the plebeians from every injury. Thus the plebeians did not fear nor did they desire power, and neither possessing power nor fearing it, the competition they might have had with the nobility and the cause of such disturbances were eliminated, and they were able to live in unity for such a long period of time.

But there were two principal causes for this unity: first, the fact that Sparta had few inhabitants and could therefore by governed by few men; second, the fact that by not accepting foreigners into their republic, they did not have the opportunity either to become corrupt or to grow to such an extent that the city became an intolerable burden for the few who governed it.

Machiavelli observes that in Sparta, significant equality of property, coupled with an exclusionary hereditary aristocracy, massively reduced the ambition of the masses — and therefore the potential to enter the next stage of the civilization cycle laid out in Chapter 2. You might be poor, but so is everyone — even the aristocrats — so what are you going to throw a revolution about?

He also notes that the best safeguard a king has for his own position is to ally himself with the masses and secure their wants and needs. Since the Spartan society was anti-property, anti-wealth, and anti-luxury, there was no possible form for this alliance to take other than one of mutual protection from harm. The king can’t lure the masses with handouts — “bread & circuses” — when fun is banned and everyone gets the same amount of bread.

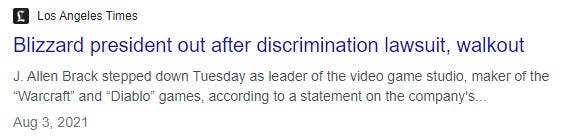

While many of the examples in this book will be social in nature (econo-/politico-/religio-/cultural factors), this idea applies to social institutions of any kind, including corporations. The analogy is strained, but if you view a State as composed of competing factions — the Elite and the Masses — then you could also view a company as composed of similar factions — Management, Employees, and Customers. My model here is:

Management::Consuls

Employees::Senate

Customers::Plebeians

— which suggests that some segment of internal stakeholders will tend to engage in power struggles against executive leadership, and that the “best safeguard an executive has for his own position is to ally himself with the customers and secure their wants and needs.”

I realize this might seem like I’m smoking my usual blend of English Breakfast Tea and chocolate, but I actually think this framework is a very useful mental model for modeling current events and predicting their likely outcomes:

In each of the above three events, having an accurate model of customer sentiment regarding the company and the exec suffices to predict the outcome (note: SpaceX’s actual customers are not average consumers like me) — arguably more so than actual financial metrics.*

On a reasonable timescale, all sufficiently successful Executives will experience a campaign against their leadership in one vein or another. Keep Machiavelli’s advice in mind, when he says “no better way to secure their office…”

*as an uninvolved party in these three examples, and a customer of two of them, I happen to also think the outcomes in each was the correct one. Which is not contrary to my point: if you haven’t satisfied your customer base enough that they would stick their neck out for you, you are not secure.

Justice Must Be Seen To Be Done

Chapter 7: To What Degree Public Indictments Are Necessary in a Republic to Maintain Its Liberty

Note how useful and necessary it is for republics to provide through their laws a means of venting the anger the multitude feels toward and individual citizen, because when such legal means are not available, they will resort to illegal ones, and without any doubt the latter produce much worse effects than the former.

The examples in this chapter are fully fleshed out, both ancient and current. They make for compelling reading.

To his point about citizens seeking their own “means” when failed by the state…we are hot off the heels of a summer of nationwide protest in response to police murder, unrest, civil disobedience, uncivil disobedience, more police brutality, police abandonment of duty, a crime wave, a homicide wave, and, in a response Machiavelli would predict, private citizens buying an extra 8 million guns:

If the republic cannot provide justice, the masses will attempt to do so themselves.

To quote from later in the same chapter:

…this would have given rise to individuals harming individuals, the kind of injury that generates fear; fear seeks protection, for which partisans are procured; out of partisans factions are born in states, from which arises their destruction.

Real Darth Vader stuff.

Whatever your degree of support for some of these things, the Machiavellian view is that they are a predictable consequence of Judicial inadequacy.

Fix the justice system and you can fix a lot of the other unpleasantness.

False Accusations Weaponize Democracy

Chapter 8: False Accusations Are As Harmful to Republics As Public Indictments Are Useful

Thus, so full of envy that he could not restrain himself, and realizing that he could not sow discord among the senators, he turned to the plebeians, spreading various sinister rumours among them…

These words were quite persuasive with the plebeians, with the result that they began to hold meetings and to create disturbances in the city; this displeased the senate, and since they considered it a significant and dangerous situation, they created a dictator to examine the matter and to hold his impetuosity in check.

We got a dictator appointed in 2 sentences. Pretty impressive speedrun there.

False accusations are most often employed where there are fewer public indictments and wherever cities are less well organized to receive them.

The organizer of a republic must find an arrangement which allows charges to be made against any citizen in the republic without fear and without respect to the individual’s position, and after a charge has been made and thoroughly examined, he must severely punish those making false accusations, who cannot complain when they are punished, since avenues were open to hear the charges against those whom they falsely chose to accuse under the porticoes.

Wherever this element is not well organized, great disorders always follow, because false accusations irritate but do not punish the citizens, and those who are irritated think about proving their worth by hating rather than fearing the things that are said against them.

To be clear, step one is to provide speedy & effective avenues of justice for all citizens at all times.

If you mess that up, everything else is suspect.

The False Accusations described in this chapter that led to a dictator being appointed were not made in courts at all — they were spread amongst the people as part of a power struggle.

The backdrop is, as usual, that these words have consequences for the health of the nation, and that the masses can always be leveraged to provide power and support that a functioning justice system would never condone. I note to myself while reading that the examples he fleshes out from both Rome and Florence involve intra-elite competition. Perhaps you can think of similar examples from more contemporary history.

This is a continuation of his theme of the balance of power between Autocratic, Aristocratic, and Democratic power: the democratic power can be easily swayed by false accusations made in public spaces (because the plebeians are not particularly smart, wise, or capable, on account of the fact that if they were, they would ascend to the elite in any worthy meritocratic society).

Our internet discourse today is as unhealthy as ever, and people of all stripes have experienced the unpleasantness of the Democratic Eye being turned on them, transforming their private messages into a stream of abuse, slurs, doxxing, and death threats. Those things are bad in all cases — but knowing that they can be summoned against your opponents increases the expected frequency of their summoning.

False accusations are a primary way elites summon those disaggregated democratic weapons against their opposition.

That’s the moral hazard of False Accusations — not punishing them swiftly and to the satisfaction of all involved results in much worse behaviour than otherwise would have occurred, at many meta-levels of society.

Urban vs. Rural Divide: Older Than You Think

Chapter 11: On the Religion of the Romans

In truth, no maker of extraordinary laws who did not have recourse to God has ever existed in any society, because those laws would not otherwise be accepted, and because although the good things known to a prudent man are many, these things in themselves lack the self-evident qualities that can persuade others.

There’s a brief hint of self-pity in this paragraph that won’t resurface until the very end of the book. The point that good and true things are often unconvincing to others is felt most strongly by a man who has tried and failed. Given the continued relevance of Machiavelli’s thoughts in this book 500 years later, I find him somewhat vindicated here.

Without doubt, anyone wishing to establish a republic at present would find it easier among mountain people, where there is no civil society, than among men who are used to living in cities, where civil society is corrupt; a sculptor will more easily extract a beautiful statue from a rough piece of marble than he can from one badly blocked out by others.

I conclude that the religion introduced by Numa was among the principal reasons for the happiness of that city, because it produced good institutions, the good institutions created good fortune, and from good fortune arose the happy successes of their undertakings.

It’s hard to come away from this chapter thinking Machiavelli anything other than an atheist, or as near as you can get to atheist in the 1500s. He’s not talking about Christianity when he praises Numa. It’s clear that the corrupt abuses of the Church are responsible for his own disdain towards “modern” (aka 1500s) organized religion, but he has many fond words for the use of religion and spirituality in ancient times to bind people together in harsh times, and gives many examples of times that the religion was directly helpful for motivating Romans to overcome hardship.

This might be interesting on its own, but the parallels to modern discourse are the most striking part of these next few chapters.

In particular, his comment here on the divide between rural and urban peoples jumped out at me. Despite being an urban ~atheist, he can’t help but note positively the stronger moral foundations that appear in rural religious areas.

“…among men who are used to living in cities, where civil society is corrupt…”

I don’t want to litigate today’s Culture War, but the durability of this rural/urban spiritual divide across 500+ years is a point in favor of these observations being systemic and not related to any facet of modern living.

Before any of my urban readers get too offended at the implication that they are “corrupt” by default, do stick around for the following chapters on Wealthy Inequality and the true nature of “real” corruption. I suspect you may see his point…

The Heresy Chapter

Chapter 12: How Important It Is to Take Account of Religion, and How Italy, Lacking in Religion Thanks to the Roman Church, Has Been Ruined

With a title like that, is it any wonder this was only published posthumously? Galileo hadn’t even been born yet and my man is here saying:

Because of the evil examples set by this court, this land has lost all piety and religion; this brings with it countless disadvantages and countless disorders, because just as we take for granted every good thing where religion exists, so, where it is lacking, we take for granted the contrary.

That is to say: people no longer expect justice in the courts, virtue in the ruling class, wisdom in the priests, and perseverance in the masses. And the lack of expectation of these things makes for a self-fulfilling prophecy. I can’t imagine how difficult that must have made things.

Machiavelli says repeatedly throughout the book that bad examples cannot be allowed to stand. Not even once. Institutions cannot pay lip service to their ideals without corrupting the whole society around them. As another wise man once said:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

To satisfy Machiavelli, a society’s elite must be both spiritually worthy and technically excellent at all times.

If we return briefly to the Lifecycle Theory of Government presented in Chapter 2, this starts to make a bit of sense: your institution is always one bad generation, or one major crisis, away from (self-)immolation, and so those with a hand on the rudder must always have the ability and the character to navigate each new challenge.

Against Wealth Inequality

Chapter 17: A Corrupt People Which Becomes Free Can Remain So Only With the Greatest Difficulty

Once a city has begun to decline through the corruption of its substance, if it ever manages to rise again, this occurs through the exceptional ability of a single man who is alive at the time and not through the exceptional ability of the people as a whole who support good institutions. As soon as that man is dead the city returns to its former habits, just as in Thebes, which, through the exceptional skill of Epaminondas, was able to maintain the republican form of government and an empire while he was living, but returned to its former disorders once he was dead.

The reason is that no single man can live long enough to train a city long accustomed to bad habits. If one man with an extraordinarily long life, or one skillful ruler succeeded by another, does not set it back in order, the lack of such men brings it to ruin, unless they have, at the risk of much danger and bloodshed, brought about its rebirth.

Thus, such corruption and so little aptitude for living in freedom arise from an inequality that exists in the city, and if one wishes to bring the city back to a state of equality, it is necessary to employ extraordinary measures, which few know how or wish to employ…

With the other contextual examples provided elsewhere in this chapter, it’s clear that the “corruption” Machiavelli refers to is a spiritual corruption resulting from divergent access to goods and services — spelled out in this chapter as Wealth Inequality. “Corruption” is used interchangeably to mean conditions of wealth inequality, as well as the downstream debased state of public character that results: “so little aptitude for living in freedom.”

This is a real thorn for Machiavelli, because he views a significant underclass who has ~nothing to their name as a huge boon for any aspiring tyrant — because said tyrant can gain the loyalty of this class by promising them stuff.

He writes:

Caesar was able to blind the multitude so that they did not recognize the yoke that they themselves were placing upon their own necks.

The use of “inequality” in this chapter is worth focusing on, as it’s obviously been a hot-button topic in American politics for the last 50 years now. Machiavelli’s utilitarian pro-liberty view is that inequality is bad because it leads to an easily manipulated population, and a malleable population will conform to the will of any ambitious aristocrat with a big enough wallet.

Inequality is the fastest pipeline to tyranny.

Institutional Corruption, Political Incompetence

Chapter 18: How a Free Government Can Be Maintained in Corrupt Cities If One Already Exists, or, If One Does Not Already Exist, How to Establish It

A sad tale of institutional decline:

This institution was good at the beginning, because no one asked for these offices except those citizens who deemed themselves worthy, and to be refused was disgraceful; as a result, in order to be deemed worthy of them everyone behaved well.

This system later became extremely harmful in the corrupted city, because those with the most power rather than those who possessed the most ability asked for the magistracies, and those lacking power, no matter how able, refrained from asking for them out of fear.

The corrupted* city moved away from meritocracy…

Rome did not arrive at this disadvantageous situation all at once, but rather by degrees, just as one falls into all the other kinds of difficulties.

…slowly…

It was therefore necessary, if Rome wished to remain free amid the corruption, that just as the city had created new laws in the course of its existence, it should also have created new institutions, because different institutions and ways of life must be established for a subject who is evil rather than good…

…and so different rules and social structures should have been setup…

But since all these institutions must either be reformed all in a single stroke as soon as it is discovered they are no longer good, or little by little before everyone realizes they are bad, let me say that both of these two alternatives are almost impossible.

…alas, having not done so, reform is the only option. And reform is ~impossible. So Rome was screwed.

The wish to reform them little by little requires a prudent man to come forward who sees this problem from some distance and in its initial stages. It is very likely that an individual of this type may never emerge in a city, and even if one were to emerge, he might not be able to persuade others of what he himself has come to understand, because men used to living in one way do not wish to change…

As for changing these institutions all at once, once ordinary methods have become wicked it is necessary to turn to extraordinary methods, such as violence or arms, and to become prince of the city and able to arrange it as one wishes. But since the reorganization of a city into a body politic presupposes a good man, whereas becoming the prince of a republic through violent means presupposes an evil one, we will discover that only on the rarest occasions will a good man wish to become prince through evil means, even though his goal might be a good one.

We will also discover that equally rarely will an evil man who has become prince wish to govern well.

From all the above-mentioned forces arises the difficulty or impossibility of maintaining a republic in corrupt cities or of establishing a new one in them, and even if one had to be established or maintained there, it would be necessary to lead it more towards a monarchical than towards a popular government, so that those insolent men who cannot be improved by laws would be held in check by their king.

To try to make them become good by other means would be either a most cruel undertaking or completely impossible.

Threading it all together, in my own words:

Institutions are the vessel through which state power is channeled, but it is the people themselves who determine whether that power will be used for good or evil. No institution can withstand an unworthy population, and a corrupt* people will slowly subvert any institution that was fitting for a worthy people. Given pre-existing corruption, the only way to get a functioning republic is to fuse it with a monarchy, otherwise the power-hungry elite will trample over everyone and everything.

But doing this requires what Machiavelli euphemistically calls “extraordinary means”…and few good men are willing to temporarily adopt “extraordinary means” to reorganize the state, while a great many bad men would happily don the Cloak of Extraordinary Means for evil ends.

While the Monarchical-Republic fusion is suggested near the end as the only real way out of the pit, Machiavelli rules this as a near-impossibility, barely ahead of the absolute-impossibility of all other options. Make no mistake — he strongly prefers that the people themselves become worthy of good government. By the time you’re talking of reforming a corrupted* people, you’re already too late.

If you’re a modern day Neoreactionary, this chapter will provide some excellent points and reading to support your positions, plus it’s 500 years old which makes it more based than anything written since the Enlightenment, with the one minor downside that the man outlining the points is fundamentally opposed to them, views them as ugly & unpleasant, and explains at length how they’re a local maxima that is almost certainly doomed to failure.

*A further note on corruption: today in the West, “Corruption” is used mainly to mean [exploiting a system for personal financial gain]. When a newspaper describes someone as “a corrupt official”, they are talking about personal enrichment. The IMF helpfully explains:

While this is not strictly counter to Machiavelli’s meaning, his use of the word is much broader. For instance, when he says:

This system later became extremely harmful in the corrupted city, because those with the most power rather than those who possessed the most ability asked for the magistracies…

It is the essence and spirit of the city (& its people) that has become corrupted here. Yes, aspiring politicians are abusing a system for personal gain. But that is a symptom of corruption, not a cause. There’s a much deeper level to things: the sidelining of virtue and competence in society. Note the conclusion of that sentence observes:

…refrained from asking for political appointments out of fear.

In other words, there was no longer a political meritocracy at work, purely because the most capable citizens voluntarily opted out of civic participation in Ancient Rome.

Why does this catch my attention?

Well what better way to launder Machiavellian Corruption into a system than to rebrand corruption itself? And so I ask myself, and you, whether or not Machiavelli would agree with the rankings presented here:

Using his definition, not ours, are the governments of New Zealand and Finland more virtus and competent than those of Singapore and Germany? Does the US government do 22 points more good for its people than the Chinese government? If we charted the relevant performance of these 6 nations over the last 50 years, whose captains have done best by their own people?

I am not asking: whose officials enrich themselves while working in public service? I am not asking: in which country would you like to be born?

I am asking: whose own elite proudly serve in the halls of their own government?

I am asking: whose active daily work has improved the state of their people the most?

I recognize this is a bit spicy, but that one simple sentence fragment sparked all this commentary from me — “…those lacking power, no matter how able, refrained from asking for political appointments out of fear.” — because I’ve been fortunate enough to spend time at some fabulous American institutions, from Andover to MIT, Wall Street to Silicon Valley, and the best people from each of them wouldn’t touch politics with a rusty 10-foot pole. You face personal reputation destruction, media smear campaigns, and debasement before donors. You must discard principle and sway in the breeze with the polls or the political machine or both. In exchange, you receive less power than a provincial administrator would have received working for any of the great powers of history.

And against all that, the private sector offers you: wealth, direct responsibility for outcomes that touch millions, prestige and a (mostly) protected life for your family.

Why would the competent people ever go near politics?

Of course the consequence of all this is that the political arena becomes dominated by “those with the most power, rather than those with the most ability,” which will regrettably have spillover effects on the rest of us.

Perhaps I’m too pessimistic here. Perhaps these institutions are unreflective of the country as a whole, perhaps elsewhere there are institutions where the very best, most competent, and most worthy people are proud to submit their names to the political arena. Perhaps I misread the caliber of these institutions and there are some other venues our country’s elite flows through, ones sufficiently different from my own experiences. Perhaps there is no such thing as a meritocratic elite in America and the Levellers got their wish. If that’s true, then my indictment is confined merely to the narrow slice of the population that I know well, and not reflective of broader society.

But if not…

No Bad Deed Unpunished

Chapter 24: Well-Organized Republics Establish Rewards and Punishments for Their Citizens but Never Compensate One With the Other

The merits of Horatius were very great, since with his skill he had overcome the Curiatii; his offence was atrocious, since he murdered his sister. The Romans, nevertheless, were so angered by this homicide that they put him on trial for his life despite the fact that his merits were so great and new.

He saved the republic, came home, and immediately murdered his sister. No matter how great a debt Rome owes him, they still put him on trial immediately.

No well-organized republic ever cancels the demerits of its citizens with their merits, but after having instituted rewards for a good deed and punishments for an evil one, and after rewarding a man for having acted well, if that same individual later acts badly it punishes him without any regard whatsoever for his good deeds.

…if a citizen who has rendered some distinguished service to his city also gains the confidence that he will be able to undertake without fear of punishment some bad action, he will become in a brief time so insolent that every element of civic life will disappear.

Here Machiavelli lays out a brief framework of criminal justice — i.e. implicit is the idea that not punishing evil will, at the margins, generate more of it via repeat offences, even when done by men who have achieved great & admirable things…and also that if the people believe success in one domain grants license to act badly in all others, it destroys the fabric of civic life, actively funnels bad actors into public service, and causes those who do great things to be viewed with default-skepticism.

If you ever wonder why ~all the powerful people are bad, ask if you know of anyone who received a pass for bad behaviour due to being a “high-performer” in some domain…

Executives Cannot Fear Reprisals For Performance

Chapter 31: Why Roman Commanders Were Never Excessively Punished for Errors They Committed, Nor Were They Ever Punished When Their Ignorance or Poor Decisions Resulted in Harm to the Republic

Even if a commander’s error was committed out of malice, they punished him humanely, and if it was committed out of ignorance, they not only avoided punishing him but they rewarded and honored him…because they judged it to be of such great importance for those who commanded their armies to possess a free and ready mind, unhindered by irrelevant matters in making decisions, that they did not wish to add to something already difficult and dangerous in itself new difficulties and dangers, believing that if they did so, no commander would ever be able to take skillful action.

The wisdom and maturity in this approach is fascinating.

Silicon Valley makes a somewhat decent showing of adopting this mentality, although lately the commentary endorsing failure (“fail fast, fail often!”) has taken on a slightly cynical and sarcastic tone.

The broader corporate world seems to do a much worse job on this front. Because executive pay is directly and heavily tied to stock performance, CEOs of large public companies experience perceived-negative outcomes due to factors entirely beyond their control (I hesitate to use the word “punish”). We could easily argue that executive pay is inflated, getting paid 6-figures should be enough for anyone, or that the executive should be paid less if the investors aren’t getting as good of a return. Many do argue those points, and I wouldn’t fight them.

But the Machiavellian lens is to ask: what will the consequences of adopting your rule be? The consequences of not-rewarding generals for negative outcomes that occurred due to unforeseeable events was cowardly and risk averse generals, who could be counted on to save their own hides in the present (aka battlefield) but not win glory for Rome.

Is it unreasonable to expect public company executives to behave any differently? How would you expect a rationally self-interested actor to behave, knowing that he currently holds the highest potential income earning opportunity of his life, and that that income is heavily dependent on factors entirely beyond his control? Might he not concern himself with mitigation strategies instead of winning glory for Rome building the best possible company?

Of course stock buybacks are just one tiny slice of the pie, and I’m happy to defend them from an investor point of view if anyone wants to argue the issue. The point is to view things from the General’s POV.

Let’s briefly check in on our favorite Tech stocks to see how they’re doing right now, for no particular reason whatsoever:

Being an executive — or even an employee — at one of these companies right now is pretty miserable. Your personal net worth tanked by 20-90% and your effective annual compensation dropped by a similar amount — but you didn’t change a thing.

Personally, I would note that the 2020→2022 period was marked by anomalous asset inflation, felt particularly in Tech stocks, and that this year’s bloodbath is more of a reversion to the mean than a true indictment of business value. But if you joined any of these companies in that time window, your compensation package was benchmarked against those inflated values. Knowing that they were inflated doesn’t change the fact that you’re now getting paid cents on the dollar.

I’m sure this news is all unrelated, but it’s also worth checking in on a favorite darling of the Tech world:

I leave it to the reader to explore how the perceived-punishments for mistakes handed out to today’s political leaders change their decision making, up to and including the willingness of capable people to throw their hat in the ring.

A Little Bit O’ Dictatorship Is Good For You

Chapter 34: Dictatorial Authority Did Good, Not Harm, to the Roman Republic; and How Authority Citizens Take for Themselves, Not That Which Is Granted Them Through Free Elections, Is Harmful to Civic Life

This, in combination, the brief duration of the dictator’s appointment, his limited authority, and the fact that the Roman people was uncorrupted made it impossible for the dictator to go beyond his limitations and to harm the city, and experience shows the dictatorship was always a useful institution.

Among all the other Roman institutions, this one truly deserves to be considered and numbered among those which were the source of the greatness of such an empire, because without a similar system cities survive extraordinary circumstances only with difficulty.

The usual institutions in republics are slow to move, since no council nor any magistrate can undertake anything alone, for in many instances they need to consult one another; and since time is wasted in coming to an agreement, the remedies for republics are very dangerous when they must find one for a problem that cannot wait.

I laugh to think that the bolded final sentence I quoted here was written 500 years ago.

It might seem strange at first to read the title of this chapter and try to picture how autocratic authority can be viewed positively by a man trying to set liberty and political self-determination as his North Star. But the examples in this chapter, and the limitations described, are very clear.

Today, we think of Cincinnatus as an aberration for putting down the dictatorial powers granted him within a few weeks…but reading Machiavelli makes it clear that the admirable thing to the Romans was the speed with which he accomplished his civic duty (competence as virtue). Putting down the powers after achieving his task was always part of the deal. To be sure, he could have reasonably held onto the powers for longer, and part of his legend is his complete disinterest in wielding political power for its own sake — but my point is that this was a cultivated civic virtue among the Romans, which he most strongly exemplified, as opposed to a norm he deviated from unexpectedly.

When Machiavelli, writing half a millennium ago, about events more than 2,000 years in the past, describes the political gridlock that overcomes republican forms of government, and their inability to respond in a timely fashion to crises…do I even need to say it? Only someone not paying attention to American politics over the last hundred years would need to ask for examples. A mandatory group project in high school likely taught you all you needed to know about this failure mode.

It is not just the slowness that he criticizes though — “the remedies for republics are very dangerous when they must find one” — when the stakes are severe enough, a republic who does not have an established custom of electing temporary dictatorial authority will nonetheless be forced to establish one in the heat of the moment (or else risk existential outcomes). And as he says later in the chapter:

Although extraordinary measures may be beneficial at a certain moment, the example nonetheless causes harm, because if one establishes the habit of breaking the laws for good reasons, later on, under the same pretext, one can break them for bad reasons…In conclusion, I would say that those republics which have no recourse during the most pressing dangers either to a dictator or to some similar authority will always come to ruin during serious misfortune.

You can read a good recent example of the downsides of this republican tendency towards gridlock and excessive deliberation playing out during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, written by Scott Alexander, here:

If your system has “putting the power down” built into it by rules and reinforced by civic values and social praise, you can short-circuit a lot of the unpleasantness described above.

The CDC comes off poorly in Scott’s essay, as it took them until October 2020 to say the virus was ‘sometimes’ airborne, and May 2021 to explicitly update its guidance that the virus was an airborne threat. That’s 10 months from the initial CDC taskforce starting work on covid for a ‘sometimes’, and 16 months for an explicit airborne update. In comparison, the WHO did not use the word ‘airborne’ until December 2021, 23 months from initial “incident management system” activation.

So if “time until correct answer is reached” is a metric you care about — and in times of existential crisis, it should be — the CDC is about twice as good as the WHO. Whoo!

Of course, the excerpt I quoted above mentioned a guy called “Zvi” — who? He’s just an uncredentialled Ivy League graduate (mathematics), internet writer/nerd, most famous for being good at a card game called Magic. He first wrote a blog about covid in March 2020. He raised the possibility of airborne transmission 1 month later, had airborne transmission as his ~primary model 2 months later, and was mocking the WHO for failing to update their guidance to include “airborne” 4 months later.

On the “time until correct” metric, that makes him 5-10x better than the CDC and 10-20x better than the WHO. I doubt even he expected it would take another 17 months for the WHO to come round.

The WHO position here was so mockable that even Nature jumped in this April, with a whole article titled: “Why the WHO took two years to say COVID is airborne”:

Zvi is not particularly special here for his insights, although he was happy to write all this stuff under his name publicly. You could have read the same stuff in many other places. Scott Alexander himself made a compelling case for aerosolized airborne transmission on March 23rd, 2020. Reading and interpreting papers is well within the scope of many Ivy League graduates’ abilities.

As Scott said above, the CDC has to optimize for more than just the truth. This is perhaps even more true for the WHO. The issue is presumably not that the people at those places can’t read papers — it’s that their bosses have multiple incentive structures. In such times a man with no power, and therefore no direct responsibility, is often more able to see the true state of things.

The competing forces that influence the institution slow it down by a factor of 10. The problem is that the incentive matrix (many individuals with competing incentives) and the responsibility matrix (whose head rolls for mistakes) are non-overlapping and non-aligned.

Occasionally no head rolls at all!

Scott wrestles with this in his Feb ‘21 essay on the poor track record of those with legible expertise, but laments that there’s no simple way to translate the truth-seeking ability of Zvi into something useful to society without diluting and corrupting his abilities. The Roman solution to this was to find a man with ability, give him temporary dictatorial power to resolve the issue, take the power away and send him back to his old job as soon as the issue resolved, and shower him with praise & prestige if he did it effectively and hastily.

It required a whole socio-cultural fabric to support it. But it was used a lot (Rome was in trouble often). It worked a lot.

A purely republican body can work through these issues with time, but in an existential crisis there is no time.

So instead, we get:

Criticism Is Easy, Leadership Is Hard

Chapter 39: The Same Circumstances Are Often Seen Among Different Peoples

[The city of Florence] was forced to wage war against those who had occupied parts of its empire. Since the occupiers were powerful, it followed that a great deal was spent on a war which bore little fruit.

Since this war was administered by a magistracy of ten citizens, the masses began to hold them in contempt, as if they had been the cause of both the war and its cost, and they began to convince themselves that if they removed the magistracy the war would end.

This decision was so disastrous that it not only failed to end the war, as the masses were persuaded it would, but once it removed the very men who had been administering the war with prudence, so much disorder followed that, besides Pisa, they lost Arezzo and other places, so that after the people had realized their mistake and saw that the cause of the disease was the fever and not the physician, they re-established the magistracy of the Ten.

This tale is worth bearing in mind for anyone who criticizes the elite (which is often me, see: prior chapter). That’s not to say that those managing a nation, a company, or any other institution are always in the right — very frequently they are not.

But it’s too easy to swing the Sword of Damocles when circumstances become painful, and a proper analysis of the situation should always untangle which factors are external and which are caused by poor leadership.

Edit: on re-reading, I think this might have been too subtle, so let me be clear: I can name a LOT of people who have criticized the Federal Reserve over the last 15 years or so. Many of them continually, across chairmen and administrations. I do personally also think the Fed — and other central banks — has made poor decisions on multiple occasions, but their current status as a centralized quasi-executive government agency with a reputation for exercising power means that people tend to turn to the Fed for solutions in any and all times of crisis. But not all problems are caused by the Fed and, more importantly, not all problems can be solved by the Fed. You can read my position here.

Democratic Tyranny

Chapter 40: The Creation of the Decemvirate in Rome and What Is Noteworthy About It; Including, Among Many Other Matters, the Consideration of How the Same Circumstances May Either Save or Destroy a Republic

The more unwieldy a chapter title is in this book, the more meat on its bones.

This tyranny arose in Rome from the same causes that give rise to most tyrannies in cities: that is, from an excessive desire on the part of the people to be free, and from an excessive desire on the part of the nobles to rule; and when they do not agree to establish a law that favors liberty but, instead, one of the parties rushes to support a single man, it is then that tyranny quickly arises.

Again it’s interesting to see how — despite being a champion of self-government and liberty — Machiavelli has no issues describing “an excessive desire” to be free. To him, the constitution of the republic must always be followed, even when pursuing good ends, such that the whole of the people will always oppose anyone who tries to route around the established rules.

When a people is led to commit the error of respecting a man because he might oppose those they despise, and when this man is shrewd, it will always happen that he will become a tyrant of that city. He will wait for the support of the people to destroy the nobility, and he will never turn to oppress the people before he has destroyed that nobility. At the point where the people realize they have been enslaved, they will have nowhere to take refuge.

This description of democratic-tyranny or populist-tyranny, depending on your linguistic preferences, may seem close to home for some.

Throughout this book, one of Machiavelli’s core theses is that the triple-tension between concentrated dictatorial power, semi-concentrated elite power, and the diffuse power of the masses is key to sustaining a healthy republic over the long-term. When any one of these factions succeeds in purging at least one of its rivals, it quickly establishes a totalizing tyranny over what remains.

I submit this analysis as a reasonable description of the various 20th century “revolutions of the proletariat” that took place in Russia (Lenin/Stalin), China (Mao), as well as the earlier events in Cromwellian England and Napoleonic France.

I’m going out on a tea & chocolate-fueled limb here, but liberal political philosophy will tend to push in this direction by default. If “The People” are not fully sovereign, they must be made so, or at least moved closer towards that outcome. Defining “The People” is of course left to the leaders of the various liberalizing political movements, but the overall trend has been shifting legible power from the elite to the masses across the world for ~500 years.*

I must confess a strong bias towards meritocracy, so anyone hoping to read a defense of Rome’s hereditary aristocracy here will be disappointed. But I think this point — balancing the tension between the elite and the masses — is not something our political philosophy has made much satisfactory progress on since Machiavelli’s time, and the base impulses of acquiring political power get in the way very quickly.

If Step One of your [Three Step Plan To Achieve Utopia] involves proscription or Dekulakization, Step Two will inevitably be a chap named Stalin sending your aunt to a Gulag because she did her job as a census worker and it turns out the numbers weren’t big enough.

The standard narrative here is that Stalin’s dictatorial power itself is responsible for this descent into Gulag-madness and mass murder.

Machiavelli’s narrative is that the dictatorial power always exists, whether you can see it or not, and is opposed and balanced by the interests of ambitious elites in society. If you remove the political class that checks Executive power…

When a people is led to commit the error of respecting a man because he might oppose those they despise-

…you get the tyrant you asked for.

Fun fact: a quick Google search taught me that the word “Democratization” was a neologism coined during the French revolution. It also turns out Robespierre was a big fan of the Roman Republic when he was younger — his own Republic only lasted 3 years before “going-monarch”, so perhaps he ought to have studied the Romans more closely.

Of course this all assumes some agreement can be reached on what achievements count as sufficiently worthy to become “elite”. Competence has many dimensions, and I’m not willing or able to lay them all out here. I make only three claims here: i) competent people exist, ii) they are underrepresented in many political arenas today, & iii) they ought not to be.

As to why it is that some part of the elite tend to play a restraining force on executive power, Machiavelli explains:

Whereas the nobles may wish to play the tyrant, the part of the nobility excluded from the tyranny is always unfriendly to the tyrant: the tyrant can never win them over completely because of their great ambition and greed, and the tyrant can never possess enough wealth or honours to satisfy them all.

He is not endorsing any of this, but describing how a state of balance may be achieved, and why the masses and the nobility in ancient Rome set about undermining the republic by trying to prosecute factional conflict against each other, allowing a centralized tyrannical power that they both endorsed — at first — to take the reins and delete their opposition.

*I am aware that, at any given historical moment, the pro-democratization side of the political divide would contest parts of this description, and some might say that wealthy/oligarchical/billionaire elite types have entrenched their own power while conceding only the trappings of power. I would agree wholeheartedly with this analysis, and would expand on it here if I had room. But by removing the publicly acceptable avenues for these people to exercise power — ways that are legible and easily contested — we left them with only two options: obfuscate their influence or give it up. You don’t need to be Machiavelli to work out which of those two is more likely.

If you wanted to remove all political power from the elite, you would need to remove wealth, fame, and any other way they might unduly influence the masses. Before you dust off your freshman-year Robespierre costume, consider Machiavelli’s lessons from this book, along with history’s lessons in the period since, about what the likely expected outcome might be.

Machiavellianism

Chapter 44: A Crowd Is Ineffective Without a Leader; and How One Should Not Make Threats First and Then Request Authority

One must not reveal one’s intentions, but instead should attempt to obtain what one wants by any means possible. For it is enough to ask somebody for his weapons without saying, ‘I want to kill you with them’, because when you have his weapons in hand, you can then satisfy your desire.

I am trying to rehabilitate Machiavelli here, but it would be remiss of me not to include this quote as it stands. He’s no fluffy bunny.

The Ender’s Game Chapter

Chapter 45: It Is a Bad Example Not to Observe a Law that Has Been Passed, Especially on the Part of Its Author; and It Is Extremely Harmful to the Ruler of a City to Open New Wounds Every Day

Without a doubt, no one could hold to a more pernicious course, because men who begin to suspect they are about to suffer some evil protect themselves in every possible way from such dangers and become more daring and less cautious in attempting something new. Thus, it is necessary either never to injure anyone or else to inflict the injuries all at once and later on to reassure men and to give them reason to calm down and to quiet their minds.

I’ve alluded briefly in other essays to the use of economic sanctions by Pax Americana to achieve geopolitical aims. For many reasons that I will probably write about in the future, I think these do more harm than good (utilitarian bad) and more evil than not (deontologically bad). But the Machiavellian lens suffices for now: never injure anyone you do not intend to immediately extinguish.

Why Colleges Take All Your Money

Chapter 51: A Republic or a Prince Should Seem to Do Out of Generosity What Must Be Done Out of Necessity

Why the veneer of charity is applied to give gifts that are not gifts at all:

This kind of prudence was well used by the Roman senate when it decided to give public funds to the men who were fulfilling their military service, even though they were accustomed to serving at their own expense. But realizing that it could not wage war in this fashion for very long, and thus that if could neither lay siege to cities nor lead troops far from home, and judging that both of those things were necessary, the senate decided to give stipends to the soldiers in such a way that they seemed to do as a favour what necessity forced them to do.

Rome was turned upside down with joy, since this seemed to be a great benefit which they never hoped to have and which they never would have sought on their own.

And the final kicker:

The senate only increased their pleasure by the manner in which they assessed the taxes, for they imposed the heaviest taxes upon the nobility, and these were the first to be paid.

I wrote a popular essay on The Uncharity of Colleges, subtitle: “How colleges make more money than God by giving it away.” The core point is that top colleges use “charity” — need based financial aid — to reduce consumer surplus to ~zero…and get thanked by students for it.

Consumer surplus is the monetary gain obtained by consumers because they are able to purchase a product for a price that is less than the highest price that they would be willing to pay.

The essay includes this table:

I was hesitant to harp on this point too much at the time, but to be explicit:

If MIT had to charge all undergraduates the same tuition, they would collect the exact same revenue by charging $25,105/year — 48% of actual tuitions.

Average Federal Government student aid is $13,120-$14,950/year, split between low interest loans and direct grants.

Under my hypothetical scenario, if your family can’t afford $25,105/year, standard government aid packages will reduce your annual cost to, at most, ~$12,000.

Under my hypothetical scenario, if your family can afford $25,105/year, your maximum payment to MIT is capped at $100,000 over 4 years.

But of course, that’s not what happens.

Instead, it plays out like this:

You owe MIT $51,520. The government helps you out with that same ~$13,000 as before, but now you need to come up with $38,500. So you go to the college, tell them you need help, they put on their Godfather costume and offer to look at your case if you show them your family’s bank accounts & tax returns, and then they “charitably” reduce the remaining $38k balance to whatever is left in those bank accounts.*

*this is a slight overstatement for artistic effect. They will often only assess 75-80% of your family’s combined discretionary income+savings.

The insane difference between $12,000 per year and $38,500 per year, over a 4-year period, has a profound impact on the economic, cultural, and psychological status of middle-class college graduates.

Back to Machiavelli: by “seeming to do as a favour” — charity — the college gets credit for doing something that it has to do anyway: charge students money. Those who receive the “aid” — 58% of students — are “turned upside down with joy.” You can read the rest of my Uncharity essay to see why colleges have no choice in the matter if they want to stay 501(c)(3).

And the kicker is that this set up, which minimizes consumer surplus and maximizes how much MIT can charge, results in the highest toll being paid by the wealthiest members of society. Again, as in ancient Rome, this causes some amount of joy among the population:

The senate only increased their pleasure by the manner in which they assessed the taxes, for they imposed the heaviest taxes upon the nobility, and these were the first to be paid.

All that “pleasure” felt by assessing the most fees upon the wealthy results directly in the insane student debt burden that the middle- and upper-middle class in America is forced to maintain.

On the surface, you receive charity.

In the background, your “class enemies” must pay the heaviest cost.

And of course, the real outcome: middle & upper-middle class savings evaporated and $1.8 trillion of student debt.

Losing Faith In The Elite Is Nothing New

Chapter 53: The People, Deceived by a False Kind of Good, Often Desire Their Own Ruin, and How Great Hopes and Bold Promises Easily Move Them

The plebeians were so incensed against the senate that they would have come to the point of taking up arms and shedding blood if the senate had not used as a shield some old and esteemed citizens, their reverence for whom restrained the plebeians from pursuing their insolence any further.

Here, two things should be noted. The first is that very often the people, deceived by a false image of good, desire their own ruin, and unless someone they trust can make them capable of distinguishing the good from the bad, this will bring endless danger and damage to republics.

When fate decrees that the people will have faith in no one, as sometimes occurs after they have been deceived in the past either by events or by men, this inevitably leads to ruin.

In this regard Dante declares in his discourse that makes up On Monarchy that the people frequently cry out: ‘Long live’ their death and ‘Death’ to their life.

Again, I am struck by how Machiavelli describes the process of shaping public opinion against the best course of action, and also by how he describes the outcome of a population who has lost all faith in its elite due to repeated prior deceptions.

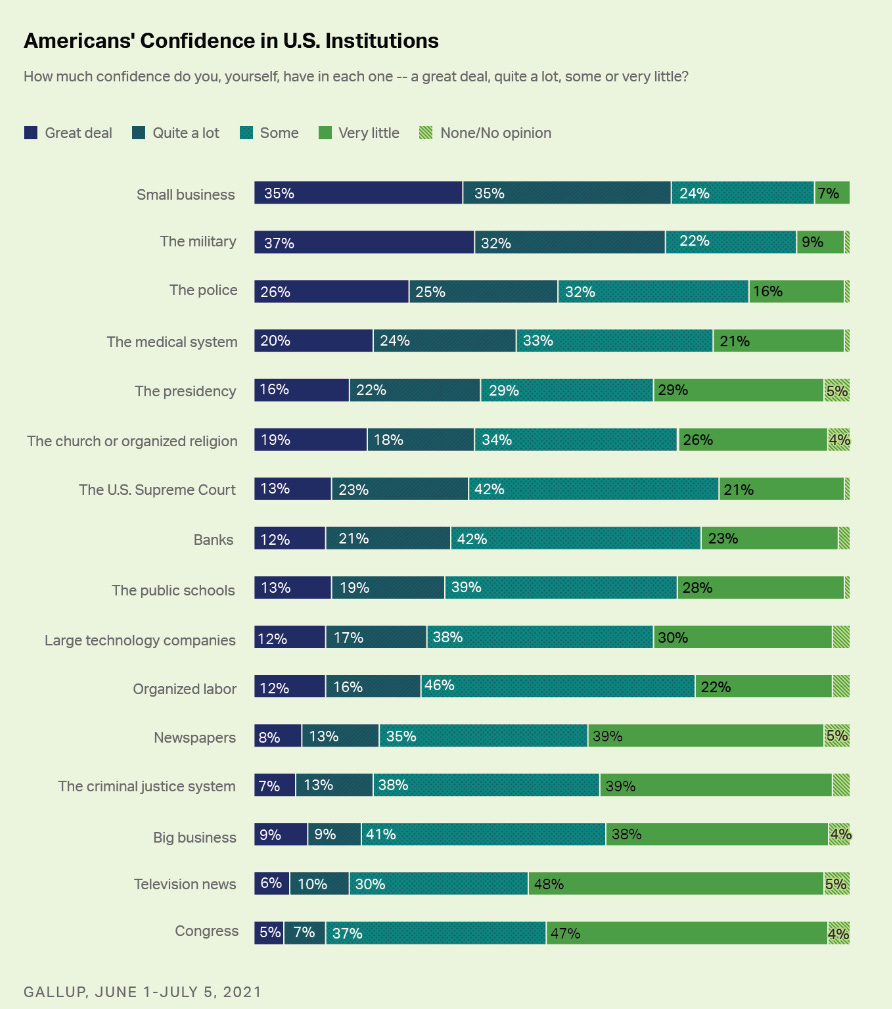

There’s no good quality opinion poll that would map neatly to “reverence for esteemed citizens”, but the overall institutional trust polls are not encouraging:

Small business and the military are the only institutions more than half the country has some confidence in.

If a sizable minority — not even a majority — of Americans became “so incensed against the senate” as to “take up arms and shed blood”, which esteemed citizens aligned with the senate would be able to go before the mob and calm them? What about the Supreme Court?

I can think of no one.

When fate decrees that the people will have faith in no one, as sometimes occurs after they have been deceived in the past either by events or by men, this inevitably leads to ruin.

No Love for Rent Seekers

Chapter 55: How Easily Affairs Are Conducted in a City Where the Populace Is Not Corrupted; and That Where Equality Exists, a Principality Cannot Be Created, and Where No Equality Exists, a Republic Cannot Be Created

Another tough chapter for the modern aspiring right-libertarian here. But again Machiavelli ties his notion of civic “Corruption” to the existence of “noblemen” and inequality:

To explain more clearly when this title of nobleman means, I will say that men are called noble who, in a state of idleness, live luxuriously off the revenue from their properties without paying any attention whatsoever either to the cultivation of the land or to any other exertion necessary to make a living. Such men as these are pernicious in every republic and in every province…

So it’s not just wealth that upsets Machiavelli, but the collection of rents without labor. If I imagine a spectrum of “Nobleman”, it seems to me that hero-to-some-pariah-to-others Elon Musk would be less far along that spectrum than an investor who deploys capital and collects its return. That is not to say Machiavelli would not also object to the existence of billionaires — you can read clearly that he does — merely that the invective he deploys in this chapter is aimed squarely at those who do not operate any revenue-generating apparatus themselves.

Collecting rents on capital is anathema to Machiavelli.

Later in this same section he says:

…where there exists so much corrupt material that the laws are insufficient to restrain it, it is necessary to institute there an even greater force, that is, a royal hand that with absolute and excessive power may impose a restraint on the excessive ambition and corruption of the mighty.

Aka Champion of Republicanism and Representative Government here supports the imposition of monarchical power in the event that an ascendant and extremely wealthy rent seeker class is strangling society. If this is hard to reconcile with his pro-liberty views, just imagine this face haunting Machiavelli’s dreams:

I think this is where Machiavelli could have taken a little more time to defend his points. The case he made earlier in “Democratic Tyranny” was very strong — that either the masses or the elite can rally behind a tyrant because of their hatred they feel for their political opponents, resulting ultimately in their own subjugation.

He does not do a good job here explaining why a monarch who would “impose a restraint on the excessive ambition and corruption of the mighty” would result in a different outcome, and all the same pitfalls would seem to apply. Given the examples he’s already pointed to by this point in the book — Numa, Epaminondas, Lycurgus — I suspect his position is that [Good] + [Monarch] is a real historical combination that exists at the founding of all great states and the only thing possible to reform “so much corrupt material.”

Obviously he has a reasonable axe to grind with the Medici and their leveraging finance to overthrow a republic, but this is one of the only times in the book he doesn’t spell out the potential downsides of a recommendation. I understand where he’s coming from —

“…hanged from his bound wrists from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body’s weight and dislocating the shoulders…”

— but as he said earlier: “we will discover that only on the rarest occasions will a good man wish to become prince through evil means, even though his goal might be a good one.”

How to Undermine A Mob

Chapter 57: United the People Are Courageous, but Divided They Are Weak

After their native city had been destroyed following the invasion of the Gauls, many Romans went to live in Veii against the statutes and orders of the senate. To remedy this disorderly behaviour, the senate, through public edicts, enjoined everyone to return to live in Rome within a certain time period and under certain penalties.

At first these edicts were ridiculed by those against whom they were passed. Later, when the time to obey them drew near, everyone obeyed.

Livy offers these remarks: ‘their united defiance changed to individual obedience, everyone having fears for himself.’

This provides helpful instruction for a republic (or any other institution) to deal with rebellious elements.

I note that Canada seemed to have a lot of trouble with their trucker friends until they were able to create individualized financial consequences for any identifiable participants (which, thanks to modern financial platforms and credit, was ~anyone in attendance).

Hopefully this taught some people why fighting the state is silly & counter-productive.

Silicon Valley’s Meritocracy, Contra the American Gerontocracy

Chapter 60: How the Consulate and Every Other Magistracy in Rome Were Bestowed Without Respect to Age

It is evident from the unfolding of history that after the consulate came to the plebeians, the Roman republic granted this office to its citizens without respect to age or family; indeed, respect for age never existed in Rome, but the city always sought to discover exceptional ability, whether it was to be found in the young or the old.

When a young man has such exceptional ability that he makes himself known through some illustrious deed, it would be a most damaging thing if the city were not able to avail itself of his talent…

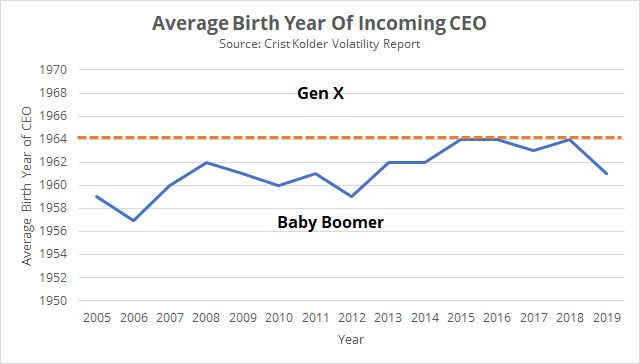

In contrast, I present some assorted data from America today:

One of the very best things you can say about Silicon Valley is that it empowers capable young people, gives them a great deal of responsibility, and lets merit play a large part in determining outcomes.

A lot of ink has been spilled over the imperfections of Silicon Valley and the various axes on which it fails to attain the idealized meritocratic outcome. While that’s all well and good, it’s hard to think of another area of the U.S. that is more supportive of ambitious and capable young people — and by supportive I mean: “actually handing them the reins of power and responsibility”.

This isn’t just about Founders either — many US Tech workers don’t realize what an aberration it is to be given personal control over economic, engineering, or design outcomes that impact people all over the world, with minimal oversight…in your early-mid 20s.

The opportunities are unmatched, and the rewards that come with them can be pretty sweet too. And for those on the other end of the deal, it turns out that talented ambitious young people can accomplish an incredible amount fueled only by takeout, flavoured water, and easy money.

Other industries should give it a try sometime.

So that was 12,000 words and I’m only done with Book I. We’ve covered 80% of what Machiavelli has to say regarding the internal affairs of a healthy republic. His chapter titles mostly suck, but I think my revised titles get the gist across.

I’m going to break it up there just to save my poor web browser. Editing this is breaking my PC. That said, the other two books combined are shorter than this section, so you’re way past the halfway mark if you made it here. I’ll link Part II here when it publishes - which will cover the rest of the book, more memes, and a little extra opining from me —thanks for reading, hope you enjoyed.