Japan’s Housing Crisis: What The YIMBYs Don’t Understand

a post-thanksgiving bounty to feast on instead of doing the dishes

What Really Drives Housing Prices — And Why Japan’s Haven’t Increased Since 1995

On a recent podcast, I noted that the world is uncertain, full of scientific studies that don’t replicate, an expert class that performs worse than prediction markets, and a complete lack of open data across all meaningful topics. If you’re a capable individual, the way to navigate this is to develop strong mental models of things that matter — and use those models to filter the horrific ratio of noise-to-signal that saturates the information landscape.

This essay is about something YIMBYs get very wrong, very often. But beneath that it’s about leaning on mental models to see through BS, integrate data with reality, and reason about causality.

Note: as usual, if you’re reading this in your email inbox you’ll need to click the title above and read on the web — depending on your email provider, the bottom 10-40% of the essay will likely be cut off.

TL;DR — A Summary of the Arguments & My Counter Narrative

YIMBYs have a wonderful narrative about Japan’s housing market

Japan removed all the housing regulations

Japan builds houses like crazy

Tokyo’s house prices have barely increased in 25 years

Thus: we should also remove all housing policy regulations and build houses like crazy

This will keep house prices down in places like San Francisco

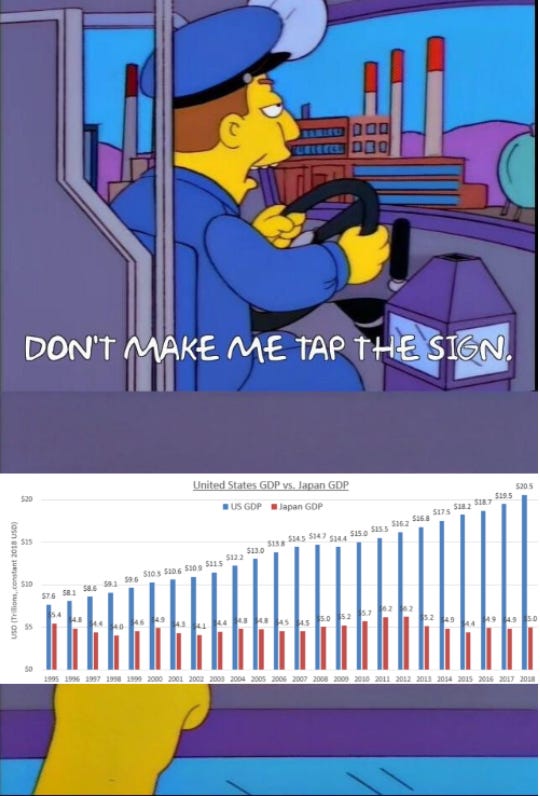

Sadly the data YIMBYs use to justify this is cherry-picked to hell and their conclusion does not follow from the data

You should ignore anyone who shows you housing data benchmarked to 1995

All the articles you’ve ever read about Japanese house price stability happen to be benchmarked to 1995

Significant housing reform went into effect in June 2002

It immediately increased house prices (lol)

This was heralded as a massively positive accomplishment by all the right people

Why? See below.

My counter(intuitive) narrative: house prices exist at the intersection of capital-available-to-spend-on-housing and supply-of-houses — it’s the money that matters, not the raw number of people

Japan suffered national economic tragedy circa 1990 and the relative immiseration of a whole generation over the last 30 years

When the people have no capital-to-spend-on-housing, it’s not surprising that house prices go down year over year for 14 straight years!

Housing policy deregulation in 2002 caused an influx of capital and development, which revitalized a stagnant market — a good thing ! — but caused prices to increase net-net due to the extra capital entering the market from both buyers & developers

Smart people who know this but want to advocate for their policy anyway will use condensed bar charts to avoid anyone asking the obvious question: “how come housing prices went down 51% between 1992 and 2002?”

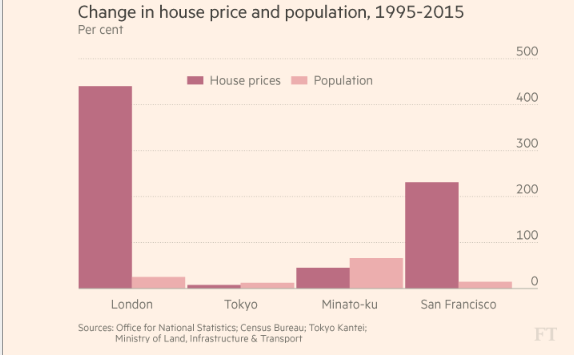

Top: YIMBY analysis from the Financial Times. Bottom: my analysis of the full data set. (click to enhance)

Of course, deregulated housing policy may in fact be the silver bullet certain cities need — this essay is not an argument for or against YIMBYism

It is simply a request to stop pretending the bar chart on the left above is a simple slam-dunk argument in favor of the YIMBY position, as opposed to a tragic output from an economic disaster

The YIMBY Weebs, Steelmanned

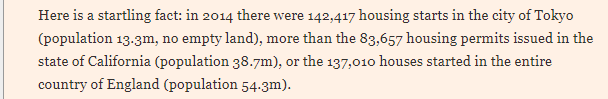

I’m not sure who the original Housing Policy Japanophile was, but many of the links I find across publications today lead back to an old piece in The Financial Times:

You’ll find the arguments and data presented in this 6 year old piece are repeated today across publications & individuals of all political stripes.

The three-point narrative is simple:

Tokyo built more houses in [YEAR] than [country/state] did:

2. Due to internal migration, Tokyo has experienced a larger percentage increase in population than [country/state] over [time period]

3. Despite the population change, housing prices have barely increased:

The data here is clear and it matches the economic theory: the price of housing is kept down despite population moving to the city because housing starts increased the supply of housing.

In this narrative, the primary antagonist of places with rising house prices is bad housing policy:

The solution to dramatic increases in the cost of housing in the West is simple: fix housing policy by nuking the byzantine “zoning rules” and corruption-filled permitting process that defines San Francisco’s real estate market, and you’ll get reasonable & affordable increases in the cost of housing over time.

I can’t speak to Robin Harding, but Wikipedia tells me The Financial Times is a centrist publication that supports free markets, free trade, liberal democracy, classical liberalism, and is considered a newspaper of record, so opposition to regulation of all sorts may come naturally to them. But you’ll find this exact same argument in Vox, which I’m told is left-wing, and the Wall St Journal, which is apparently also centrist (though I think many would say leans right?).

If you follow me on twitter, you may have seen me interact more recently with folks associated with the Institute for Progress, Bloomberg, and various other accounts that are re-telling the same story to their audiences.[0]

If you found the above narrative compelling then I did a good job with the steelman.

Counter(intuitive) Narrative: The Steel Man’s Rust

Contrary to the 2016 Financial Times analysis, Japan does not show a happy tale of deregulated housing policy solving a crisis.

Instead it tells a tragic tale of relative national decline.

I’m here to present a more complex but more accurate story: that it’s the supply of capital available to spend on housing — money, not people — that interacts with the supply of actual housing units to determine prices at the end of the day. Increasing the supply of housing may apply downwards pressure on prices, yes…but a national economic collapse that lasts 30 years, destroys wages, reduces residential home prices by 90% in some neighborhoods over a 10-year period, flatlines GDP, and bankrupts a generation will also apply significant downwards pressure on housing prices.

Celebrating a recession for keeping prices down is not, generally speaking, the behaviour of people who support Progress. In most contexts it’s considered ghoulish. Only someone intensely wedded to policy advocacy could be blind to the importance of these otherwise obvious contextual factors.

The grandest irony of confusing Japan’s economic collapse for a triumph of policy is that, to the extent that housing policy did have a neatly-demonstrable immediate impact on Tokyo’s housing prices in the last 30 years…it clearly increased them. And it’s a good thing that it did. And it was celebrated at the time by a who’s of who of smart people.

If that doesn’t make any sense, give me a few minutes to explain..

The Problem: Just-So Stories

There are two keys to this puzzle.

The first, which in this case came before I dug into the data, is my basic worldview that “Comparative International Economics for the Purpose of Identifying Good Policy” is a mostly fraudulent activity.

This is not an iron rule of the universe — you can do some pretty good analysis on international economic data. Sadly, most people don’t. The people doing the analysis in the first place are usually looking to identify an example that proves their preferred policy position and not to uncover some juicy nugget of truth.[1] “Correlation is not causation, except when I really like the policy.” I don’t intend to convince anyone of this somewhat spicy take in this essay, only to show how it changes the interpretation of data presented.

The second key, which is only the sort of thing you might notice if you already have a skeptical worldview of “just-so” international comparisons, is that the original Financial Times article chose 1995 as the starting point for its data.

Despite choosing that specific date, you can read every word of the piece and not find a single mention of that date. In fact the only mention of “199X” is this sentence:

Which, yes, highlights the deregulation of housing policy (hey! that’s the policy we want!)…but instead points to 2002 as the ideal starting point for our data. I’m not kidding that this is the only mention of a specific date in the whole piece. Isn’t that strange?

If you go through every other link I’ve posted above to all the various other analyses that have been done on this topic, all the other sources, many of them citing independent research and not the Financial Times, you’ll find again and again they choose 1995 as their starting point. Curious. The Wall St Journal piece is the most circumspect of the bunch, using the phrase “near the turn of the century” instead of a date at all.

Why?

Perhaps there's some massive policy change that occurred in 1995 that the Financial Times missed? Perhaps everyone else missed it too or just forgot to mention it?

Why is it always 1995?!

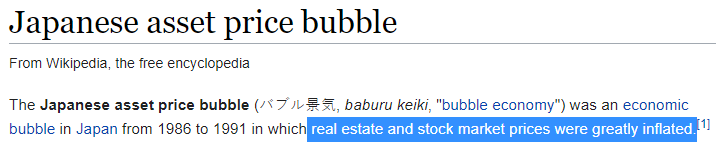

The Lost Decades: Japan’s Economic Woes

If you get into the habit of looking past high-level macro data and resisting the urge to draw “just-so” comparisons, you become familiar with the underlying data and the many drivers at play.

For those unfamiliar with the magnitude of this bubble — and the resulting carnage wrecked upon Japan’s economy in its aftermath, I’d like to highlight the performance of the Japanese stock market since the year 1990:

I’ve added my signature MS Paint red dotted line to highlight the beginning of the year 1995, at which point asset prices (housing) is now fair game for the YIMBYs to start tracking. I’ve also added a rare blue dotted line to mark the date of the original Financial Times article.

Of course, stocks are not houses. But the full time series data of the Japanese stock market tells a richer story than a simple bar chart of “change in house price” can. You can see the protracted collapse play out over the years.

Trying to find an accurate time-series view of average Tokyo house prices proved incredibly difficult (worldview: because it reveals a story that does not neatly support YIMBY housing policy & few others are writing about this topic), so I created it myself from data provided by The Land Institute of Japan:

Real world data is always messy, so my source here only provides Tokyo housing price data since Q1 1992, but I hope the similarity between the graphs of housing prices and stock prices is apparent.

Again, the question must be asked: in Q2 of 2016, why would you choose 1995 as your starting point?

Obviously the stock market doesn’t cause housing prices anymore than ice cream causes drowning. But there’s a shared underlying driver of these two things, and that driver is not housing policy.

Choosing the Right Tone: Tragedy & Misery

Reading tone into written English language can be a challenge for native & non-native speakers alike.

That said, as you read coverage of Japan’s economic misery post 1990, whether on Wikipedia or The New York Times, the tone is clearly one of professional sympathy and commiseration. Consider the language from the wiki here:

If you were looking for “just-so” stories of a country to compare against your own, the description above would not be encouraging.

And yet the Japanophile Housing Policy advocates believe that it is the exact time period and location described in that quote — “by 2004” — that should be emulated. If housing policy did this, you ought to want no part of it.

If.

Most of my readers are old enough to remember 2008, and therefore to have some mental model of why a massive and sustained crash in the price of the primary asset purchased by households — and one purchased predominantly with debt — is bad for regular people. But the following New York Times article from 2005 provides an eye-widening slice-of-life look into a bygone era — you really can’t miss a single word:

A government employee who becomes trapped in a prison of debt.

“a 14-year trough” is described with sympathy & horror in the year 2005 — matching the data I showed above. Read the article to learn how many bankruptcies per year were occurring as a result. Compare to the tone in the Financial Times 2016 piece.

Bitter. Spiraled downward. 14-year trough. Homeowners biggest victims. Avoid property.

Thinking the data output from this disaster is positive because of a single metric chosen at a specific point in time that happens to be central to local policy debates 5,000 miles away is the econ-journalist equivalent of not talking to your users.

A whole generation — millions of individual Japanese — lost their life savings and suffered through an economic stagnation measured in decades. As of 2020, the period referred to as Japan’s “Lost Decades” was recently extended to the last 30 years, up from the last 20.

The real nugget in that New York Times article though, beyond the tragedy of Mr. Nakashima and the irony of Mr. Bernanke, is the final sentence I highlighted:

Only recently did Japan finally find ways to revive the real estate market, by using deregulation to spur new development.

Question: in this NYT article from 2005 about the sustained collapse of housing prices, which cites economists, central bankers, and private banking executives, what does the word “revive” mean?

Does it mean that housing prices are now, finally, after 14 years……falling further? What is being “revived”?

Surely they aren’t suggesting that “using deregulation to spur new development” led to housing price increases? Right?

The Irony of Seeing Like A State

Thus the grand irony of today’s YIMBYs celebrating a 30 year old economic collapse as a sign of policy successes.

In the early 2000s, 15 years of housing price declines had left a whole generation underwater and drove millions of bankruptcies. The grim part of this tale that I cannot highlight tactfully is that Japan’s “suicides-above-expectations” during this period is measured in six figures. That’s one chart I’m opting not to reproduce here.

As the Financial Times noted, Japan’s Urban Renaissance Law was passed in 2002, not 1995.

And as a result the New York Times then wrote, and this quote could not be more perfect for my Counter(intuitive) Narrative:

If you’re not chuckling while reading this, I’ve done a bad job somewhere in this essay.

“Seeing Like A State” is to see things at 30,000ft and believe you have uncovered a simple solution to a complex problem. Contact with reality is usually painful, but the people responsible tend to have moved on by the time the pain becomes apparent, free from the consequences of their actions.

When various housing policy advocates point to Japan’s house price stagnation since 1995, they’re drawing your attention to the yellow line here and attributing it to policy changes that were made…in 2002:

In the prior section I tried to highlight that this is in fact a story of national misery with a much deeper root cause than housing policy, and that celebrating it today to score points in a policy debate 5,000 miles away is unwise & unbecoming.

But here I just want to point out the sheer silliness of this chart — and of choosing 1995 as a starting point. What a coincidence it must have been, in 2016, to pick the point on the downwards slope from 1990 to 2002 that happened to ~match then-current housing prices. My own answer to the question of “why 1995?” is that it offers: a) the appearance of an arbitrary number (ends with a 5!) and b) provides an output that seems plausible enough to pass the gut check of readers who support the policy being advocated.

Using Q2 2002 at a starting point (the time major housing policy reform went into effect!) would mean using the inflection point in the housing market — suggesting deregulation was ~causal to housing price increases and completely defeating the point of writing about Japan in the first place (FT subtitle: “Can Japan’s capital offer lessons to other world cities?” Answer: yes, but not the kind of capital you’re thinking about). And so. We cherry-pick a date that offers the strongest-reasonable data to support our preferred policy…and 6 years later people are still using it.

(Now you see the Wall St Journal’s professional savvy here if you read their version of this story: “near the turn of the century” is their wonderful load-bearing sentence, which removes the need to use any exact dates at all. While I find the subterfuge distasteful, I can’t help but uprank my opinion of their technically-correct specificity — someone there noticed the dates didn’t line up)

The New York Times piece quoted above, citing economists, real estate executives, and Ben Bernanke, notes that the sum total of first-through-nth order effects of housing policy deregulation in 2002 was a revitalization of the real estate market, which they celebrate by pointing to the first price increases in 15 years!

That is a very different story. It results in a very different graph:

You can use data to tell whatever story you like. If you’d like to challenge my own presentation here, feel free.[2] I’ve gone to some lengths to make all my sources available and to make my reasons for choosing June 2002 here apparent. But housing prices are downstream of so many factors that any “neat” narrative should be viewed skeptically.

I am not making any positive claims in this essay. I am not saying any given central banker is culpable or not. I am not saying Mr. Nakashima made good decisions. I am not blaming the people for purchasing homes to live in.

I am just asking the YIMBYs to stop using Japan as their ideal model. To stop claiming that housing policies that came into effect in 2002 are causal of a pattern that began in the mid-1990s, contemporaneous with one of the most protracted international asset collapses in recent decades.

I am asking the YIMBYs to stop using Tokyo as an analogy for San Francisco without understanding what caused the movements in these charts above — and how the average Japanese who lived through it feels about this time period.

Seeing Like A Craftsman

I am asking the YIMBYs who post charts like this:

To ask themselves: at what point in this chart did housing policy change? What was the impact of that change? What was the trend before that change occurred?

To ask: How come the period from 1980 through to 1992ish seems to have an insane increase in the price of housing? Is housing policy responsible? If not, why not?

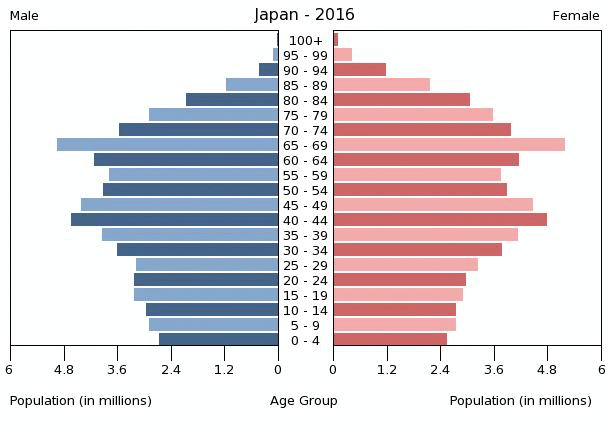

What else has not increased at all for 25 years in Japan?

How healthy is Japan’s population growth? What does their population pyramid look like? What might that mean for the number of 27-45 year-olds looking to purchase property in urban areas today relative to Japan’s overall economic productivity?

How easy is it to immigrate to Japan?

What are the job prospects for an aspiring 30 year-old Japanese homeowner today? How were they in 1980? How about 1995? How about 2005?

How have Japan’s imports and exports tracked since 1990? What percent of US imports does Japan fill? What would the impact of those changes be on the Yen? What ripple effects might that have on their economy?

Here’s a chart of the month-over-month change in Japan’s housing starts since 1980:

Looking at it, I would ask: why did new housing starts see a sustained 20% month-over-month decrease in 1991/2? What period of time saw the greatest sustained month-over-month increases in new housing starts — and why was it in the 1980s?

Why is Tokyo the most expensive city in the world to build new construction in?

And why is it perfectly natural for that quote to specify that the reason Tokyo construction is expensive is because a lot of it is happening?

How many homes does Tokyo build for every one home demolished?

Why does Tokyo’s housing cost 8x more per square foot than San Francisco’s?

Why has Tokyo’s housing become more expensive in the last few years?

What did Bloomberg mean when they cited Naoko Kuga of NLI Research Institute as saying “while the overall number of ‘power couples’ is small, their willingness to spend is strong, and their impact on the consumer market cannot be ignored,”?

What might that imply for San Francisco, where a small portion of the market become millionaires every time an important company gets acquired? (shoutout to my two friends at Figma, pls keep me in your thoughts)

I realize this is an insane data dump at the end of an essay, structured as a series of (pedantic) questions and without a clearly articulated narrative linking them all together. In fact the answers to some of them point in opposite directions. It’s bad writing on my part.

But that’s exactly my point — and appreciating this point unlocks the worldview stated at the start of this essay:

“Comparative International Economics for the Purpose of Identifying Good Policy” is a mostly fraudulent activity.

The alternative to “Seeing Like A State” is Seeing Like A Craftsman — and there is no shortcut to mastering a craft. Metis must be mastered, only episteme can be shortcut. You need to understand the answers to all the above questions and more before you can throw a bar chart up comparing Tokyo’s real estate prices to San Francisco’s and say one city should copy the other’s policy to fix all its problems.

There’s a wonderfully complex chain of factors impacting the amount of capital available to spend on housing in any local region. The Japanophile YIMBY looks at the supply of housing units and discounts the other side of the equation: the supply of capital.

Let’s discuss that equation for a minute…

Ceteris Paribus: Basic Economics

When objections to using Japan as an example of the benefits of housing policy are raised, new arguments are often thrown back as counter-objections. Basic economics teaches that most markets find an equilibrium between Supply and Demand.

Increasing the supply of housing, ceteris paribus, will put downwards pressure on prices.

Am I suggesting basic economics is wrong?!

On the one hand, yes. On the other hand, no.

The basic economics I propound is:

The price paid for housing is not at all proportioned to what the seller may have spent to improve the housing, or to what they can afford to take from the market; but to what the worker can afford to give. — Adam Smith, Book I, Chapter XI, The Wealth of Nations (paraphrased)

The supply of capital available to spend on housing — money, not people — is what the market clears against the supply of housing. Tokyo’s population may or may not have increased across any given period — but it’s their aggregate capital that matters most. If population doubles but average household wealth drops 50%, the math becomes more complex — the cost of building marginal housing units to house new families balances against a lowered ability to pay at the median.

Understanding how this plays out across a whole regional economy provides insight into why it is that regions tend to be dominated by a single industry, and also into what Naoko Kuga meant in her quote above about ‘power couples’: the most productive workers can afford to give the most, thereby ‘setting’ the marginal value of housing and the hourly value of a construction team.

“Deregulation revived the Tokyo land market,” said Toshio Nagashima, executive vice president at Mitsubishi Estate, one of Japan’s largest real estate companies. He said the changes were one reason his company committed to spend $4.5 billion by 2007…

That’s $6.5 billion in today’s dollars.

And so we see that the ceteris is not paribus. The housing policy changes made for a much better investing environment and capital flows increased. Net-net, prices went up.

Before this occurred nobody could have said whether the increase in housing supply would outweigh the increase in capital flows — indeed the NYT narrative is that a lot of other things were tried first, suggesting the experts initially believed deregulation would continue to put downwards pressure on the housing market!

In the real world the ceteris is never paribus. The idealized role of policy is to navigate the changing landscape and do what’s best for the people, balancing short and long term considerations.

What About All The Other Economies That Actually Do Support YIMBYism Through Clear Empirical Data?

I don’t know. This isn’t an essay to convince you to be YIMBY or NIMBY. It’s about why Japan is an awful example to use for “policy success on the basis of sustained housing price depression” and a plea to go find a better one.

Japan, I know a little about. Not a lot. I’m sure I’ve missed things that matter. But enough to know that the simple causal narratives are statistical misdirection at best.

My worldview is that most other nations will have their own quirks that drive housing prices much more than any given housing policy, but that housing supply does matter on the margins — particularly for centers of economic activity that attract productive workers.

I made this chart below in a Twitter back & forth to highlight the relationship between house prices and available capital (proxied as House-price/income vs. GDP/capita):

By itself this chart may not convince the already-skeptical. The R^2 suggests ~13% of the variance in housing-price-to-income-ratio is due to GDP, although removing Portugal, New Zealand, and the Netherlands boosts that to 26%. P-values on the fit are <0.05 (10^-12 order of magnitude).

And yet, once you’ve thought thoroughly about one housing market it becomes easier to reason about others. And once you start thinking about removing an outlier or two, you start wondering why those outliers deviate from the trend in the first place…

Why does removing Portugal and New Zealand improve the R^2 so dramatically? Are there any reasons they might have much higher home prices than their GDP/capita would otherwise suggest? Is it possible “national income” may be missing some of the capital interested in these housing markets? I leave this as an exercise to the reader — don’t check the cheat sheet (or the weather forecasts).

Perhaps one of these dots hides a perfect comp for San Francisco — it’s very possible. All I suggest is that every single one of them has just as much localized context behind their home prices as Japan/Tokyo does.

Why Do You Hate YIMBYs and Progress?

One of the quirks of modern writing is that criticizing one’s outgroup is subject to a complex series of socially-sanctioned checks and mostly used to wage political/cultural war on one’s enemies.

I suspect people who don’t get this far in this essay will assume that’s what this essay is, though beta reader feedback has convinced me to make my points clearer in the summary at the top, somewhat spoiling the grand reveal: when it comes to most American cities, I am of course a raging YIMBY.

In reality, my own YIMBYism rests on much firmer principles than cherry-picked data sets from an often-exoticized country 5,000 miles away purporting to show house price stability.

If I truly believe my own paraphrasing of Adam Smith about house prices being a consequence of “what the worker can afford to give” — and if I truly care about Progress, as measured by the classic yardstick of “number go up” — then it follows logically that I support house price increases to the extent that it signals the creation of underlying economic surplus. And so I would never use stagnant house prices to justify any given policy — even if house prices were a hot button issue among a left-learning urban electorate and I cared a lot about the policy in question.

When presented with data showing near-zero increases in house prices over a 25 year period, the worldview I’ve tried to articulate here will assume economic catastrophe instead of policy perfection. The city I picture looks like Detroit, not Singapore.

Naturally, the lowest effort way to get house price stability is to cap “what the worker can afford to give.”

This can be done directly via hard-caps on prices, or even on worker income itself. It can also be done indirectly by limiting or otherwise obstructing the economic progress of specific population segments and reducing the number of people willing to live in the city. One could view San Francisco’s entrenched NIMBYism through this lens with some justification. I suppose you could also engineer a recession and achieve the same outcomes.

Readers of my popular essay on the structure of Germany’s economy will notice a similar worldview of mine popping up here:

Price stability, of course, explicitly favors the existing market equilibrium. It is exactly by radically disrupting “price stability” that China was initially able to build its international Manufacturing Powerhouse.

It is a failure to maintain “price stability” that so wounded Japan’s electronics industry.

Nobody wants "price stability” until they are on top — and then they want it very badly.

Of course this doesn’t map exactly to housing, but you can see where it rhymes. The YIMBY consensus is that NIMBYism accentuates housing price inflation and that more stability could be achieved by deregulating zoning & promoting more development. The Maastricht criteria specify that new entrants to the European Union cannot promote industrial development more aggressively than existing member states, such that it would impact price stability (aka cause lower prices). Housing YIMBYs want to unleash market supply to promote stability on prices currently undergoing inflation. Maastricht wants to prevent increased supply from unduly lowering currently-stable prices.

Both view price stability good and increasing supply as lowering prices.

In both cases, I raise an eyebrow at the privileging of “stability”. In both cases, I am more interested in the actual policy impact than the intended policy impact.

When I see a chart like this:

I think “good” — Mr. Nakashima, or someone like him, was eventually able to move to the big city. To relocate somewhere more productive. To get that higher paying job he hadn’t been able to get for 15 years because his house was underwater and he owed the bank $300k.

What I love about this analysis is that constructing an alternative narrative where “deregulation keeps prices lower than they otherwise would have been due to supply increases” is nonsensical — the factors driving price increases in this market are themselves downstream of the deregulation!

“If Japan hadn’t been building housing as aggressively as it has, then the slope of that line would be even steeper!”

I used to believe this — the ultimate Motte above the Bailey of rebased-1995-housing-price-bar-chart nonsense. But the story told in this essay is that housing policy changes were responsible for reviving Japan’s flatlined housing market. How could the slope of the line have been more positive? It was negative!

Recall the state of Japan’s economy from 2002-2012 and ask what factors could possibly have driven a steeper increase in housing prices than shown in the chart above given this backdrop:

Pictured: zoomed in snapshots of Japan’s stock market (above) and average wages (below) from the 2000-2012 era, marking the first decade of Japan’s “housing market revival”.

This is not an era whose economic backdrop suggests rising asset prices are the default expectation, although the stock market looked promising until 2008. Perhaps it’s possible that, absent housing policy deregulation, Tokyo’s house prices could have gone up even more than they did. I’d love to see a thorough analysis of all factors here, though we can never go back in time and run the experiment again.

Looking at the chart above, Tokyo’s housing price increases have been remarkably consistent for a decade. If we grant that it was housing deregulation that “revived” the housing market and ultimately led to housing price increases…my question becomes: at what point in time was the slope of price increases then subsequently suppressed by the exact same policy that allowed for price increases in the first place?

If you take these hypotheticals to their extremes, I do expect you’d see behavior that converges on simple economic models of supply & demand. But the actual process of adding net new individual housing units was not, from 2002-2022, a hypothetical process. It was one fueled by developer investment and everything else that entails. No one expected the result of deregulation would be saving the housing market…eppur.

A Productive Future

I believe a functioning city should be a growing city. It should be a gravity well of talent and productivity. And the more productive people come together, the more network effects amplify their output.

Housing supply should increase to try and meet this demand. But if productive people cannot create economic surplus faster than real estate companies can create housing, that says something about the potential returns to their economic activity. If you’re curious what it says, look up the historical rate of returns of real estate and compare them to equities or other investments.

Recall that the most-productive market segment have an outsized impact on the housing market. Ideally your shining city is more productive than a REIT.

But if your most productive city is more productive than real estate developers, and if housing prices are disproportionately impacted by the most productive workers in a region, and if housing is determined overall by “what the worker can afford to give”…then to become overly fixated on housing prices as the singular goal of policy is to come into conflict with Progress itself.

Definitely Not Talking About Actual Policy In San Francisco

Of course the housing policy situation on the ground in places like San Francisco is complete insanity. That goes without saying. It’s hard to imagine the immediate impact of increasing San Francisco’s housing supply by 10% not being a drop in the price of housing there. But San Francisco should be granted the same respect I granted Tokyo in this essay — a full & proper understanding of the various factors in play.

Note this is not the same as “listen politely to your political enemies” — but it does mean asking how the supply of capital available to spend on housing has increased over the last 2 decades. It means asking uncomfortable questions about Wealth inequality and bifurcating social class in the Gold Rush city — and how the impact of increased capital on housing prices interacts with the distribution of that capital and city residents. It means asking about the future career prospects of the various people involved in blocking the YIMBY agenda — from on-the-ground voters to low level corruption to high level obstruction. It means asking why the political positions that implement policy are anathema to San Francisco’s newly-minted wealthy, who relegate themselves to donating and organizing and tweeting. And other such pointed questions.

If San Francisco had a very different set of policies, many more of my friends would currently live there. That would be a good thing from the perspective of building “productivity gravity wells.” But how it would impact the housing market over the long term, net net, is a murkier question.

A full exploration of all these questions is far too close to home and best left to the reader. I recommend a pairing of English Breakfast Tea & chocolate for said exploration. If none is on hand, I suppose whisky will do.

If just one reader comes away from this essay and encounters in the future a YIMBY pointing to the Japanese real estate market from 1995-[DATE], and recognizes that policy-based causation cannot be easily drawn from a period that overlaps with economic stagnation…I’ll chalk this essay up as a success.

But beyond that, my real hope was to show, not tell, how to navigate a hostile information landscape by building a fleshed out mental model of what’s going on under the hood — and then turn that mental model into some quick & easy heuristics that can save you time, energy, and effort. You build those functional mental models by diving into the details and trying to see how they fit together, not by starting with some high level principles and doing abstract reasoning.

When very smart people end up being very wrong about a topic, it’s usually because they skip doing the schlep work themselves and rely on abstract reasoning and outsourced opinions.[3]

If you read this far — thank you. Allow me to leave you with a parting laugh:

Notes

[0] I searched for articles covering this topic and narrative from the usual right-wing news publications…but I couldn’t find much. Let me know if you did. Here’s The Cato Institute quoting the WSJ article above and The Manhattan Institute obliquely referencing Japan’s zoning laws. One guess is that the housing-policy woes that breed YIMBYism are a feature/bug of center-left-leaning urban areas and that the average right-wing news reader can probably build a pig farm in their backyard without a permit — but that’s just my worldview talking and I’ve little data to support it. Certainly Cato & Manhattan institutes take it for granted that their audience supports housing deregulation and needs no convincing.

[1] This ought to be the default worldview of anyone being presented with a “just-so” comparison between nations. It can be explored and shown to be a justified or unjustified bias only by digging into the fundamental drivers of the data for each & every nation. (Such a blanket dismissal is a reasonable position to begin with because no two nations of international importance are ever sufficiently similar to merit a direct comparison between individual policies)

I realize to those who are used to consuming studies and data provided by reputable publications this level of skepticism, cynicism, and default-distrust likely seems crazy.

I suspect even those readers I convince on this one specific topic will not become so cynical as to adopt the worldview I’m describing here. I would not ask anyone to. Adopting blanket distrust only works if you can rebuild functioning three-dimensional models of your own — and that takes time, effort, and a willingness to stop “seeing like a state.”

The hazards of this worldview are many. Communication is tougher: your narratives aren’t neatly packaged stories anymore. You make opponents out of all the conflict theorists by default, plus the mistake theorists you’re arguing with. You are more susceptible to default-contrarian conspiracy-style narratives. If you become a flat earther because you read this essay, don’t blame me — let me know if you get past the ice wall!

And the benefit of seeing the world this way is simply that you’re more likely to notice groupthink and poor reasoning — and then go looking deeper yourself. Really, you’re just signing up for more work. Hardly worth it.

[2] Looking at my own charts here, an attentive reader might ask: why did you choose your benchmark to start in 1992? What makes that more fair than 1995? Aren’t you just doing the exact same thing you accuse the Japanophile YIMBYs of?

This is a good question.

The answer: 1992, or perhaps a year earlier or two depending where you look, marks the top of Japan’s asset bubble. The core thrust of my point is that the 1995-Present benchmark includes a 15-year-long asset slump due to the bursting of that bubble (& the general deterioration of Japan’s economy). Any pricing analysis of assets in Japan must be anchored in that reality.

So because I want to tell a story about the aftershocks of a bubble popping, I’ve started my analysis at the height of that bubble. The asset prices at that peak may be unreasonable, but their unreasonableness is obvious when looking at the charts. Selecting a point halfway down their slope — 1995 — allows for misdirection.

“Housing policy drove a 33% decrease in Japan’s house prices” is a statement that the average Financial Times reader is unlikely to swallow hole. Especially if they happen to be a cosmopolitan citizen familiar with the expense of living in Japan.

“Housing policy stopped house prices from increasing more than 5% over the last 20 years”, on the other hand, is a much more easily digested tidbit — especially for an audience already pro-housing deregulation and pro-building-things.

One counter to my own narrative is to stretch my charts further back. Extend the data to before the bubble began. To compare the slope of Tokyo’s housing price increases from 2002-2020 to some period from 1950-1970. Perhaps there’s some divergence there that could provide strong support to using Japan as a shining example of YIMBY success?

Let me know if there is and perhaps we can convince people to stop using the 1995 data.

So to this point, shoutout to the twitter account @ne0liberal for nearly doing this after I wrote this essay’s first draft:

I have no idea what’s happening in South Korea — perhaps they are the perfect example the YIMBYs need and not also a victim of the late 1990s East Asian Financial collapse? Either way, the pyramidal shape of Japan’s home prices in this chart prompts absolutely no interrogation from the poster. While their numbers don’t tie exactly to my own, the shape of them is similar. The suggestion is that, despite some increases in nominal income, home prices decreased an incredible amount and then flatlined in Japan.

The implication, for those who follow these debates, is that housing policy is responsible for this — and it’s a good thing.

If you’ve read my essay, hopefully you now understand: not only did unrestricting housing policy not do this, it was implemented a decade after one of the most significant asset collapses in recent history began and was responsible for finally starting to increase house prices in Tokyo. All these charts show for Japan is that its economy blew up, and then people moved out of the countryside and stopped having kids.

That said, this image contains some original analysis instead of cribbing off everyone else’s 1995-based analysis, and so I give the poster much respect. Ideally we could look at Tokyo’s housing price increases from 1945 through to 2022 and then compare and contrast with underlying economic and demographic data.

[3] I write this knowing full well that the analysis done in this essay is insufficient for any meaningful academic discussion! A proper PhD would do the full analysis described in note [2] above, controlling for the variables I merely allude to controlling for. In my allusions I am doing what I chastise others for: relying on abstract reasoning to reduce my burden of work. I trust those who think sufficiently similarly to me can follow my reasoning — and I am hopeful those who disagree will take on the burden of doing a proper PhD thesis on the topic. Send the preprint my way if you do!

My only defense here for my laziness: I have to leave some research topics for the real econ students.

[99] I claim the right to call them “YIMBY Weebs” by virtue of self-identification. If you don’t need to click that link to work out what a “weeb” is, you might enjoy my essay about anime, an ancient Cathaginian god, and the limits of human self-sacrifice.

[99-2] A friend asked me after my last twitter argument on this topic: “why do you get so worked up about the YIMBY-Japan stuff? It clearly bothers you more than other things people are wrong on.”

This is true and I see no reason to hide it.

There are two main factors:

The reality of life in Japan is not utopian: the “salaryman” lifestyle is horrendous and most Westerners would run far, far away from it. The smart, ambitious, hard-working youngsters would all be materially better off if they could move to a major US city and get a job there, housing policy woes included. Additional difficulty levels are applied for women & non-Japanese.

A high school friend of mine ended up doing investment banking in Tokyo: an experience significantly worse than investment banking in New York.

While the specifics may vary on the margin, if you want to live & work in Tokyo you should assume:

You get paid lower wages than your comparable US employee

You work 10-60 hours per week more than your US counterpart

You live in a smaller apartment than your US counterpart

You spend an equivalent portion of your salary on rent as your US counterpart

For readers familiar with elite American wages, a fresh 2022 Investment Banking Analyst at Goldman Sachs & a Software Engineer at Google both make about $75k/year in Tokyo

If either of these companies offer to pay you that amount per year in San Francisco, you made a serious mistake somewhere

Exoticizing Eastern countries for some specific policies they enact within the broader context of their national cultures has been a pastime for niche Westerners for decades. It’s mostly frowned upon in polite company for playing on the audience’s stereotypes.

“Copy Japan” is a fine strategy in many arenas for anyone with executive responsibilities…

…but public policy advocacy that’s reduced to a simple bar chart and the slogan “copy Japan” plays too close to tugging on stereotypes for my comfort — where the average reader is supposed to deduce that the Japanese have figured something clever out long ago because, well, of course they would, right?

It’s the juxtaposition of these two factors that provokes me. An underlying tragedy held up and celebrated because it delivers a surface-level metric that’s appealing to a distant audience. A lack of interrogation of data because, in the best case, of confirmation bias or, in the worst case, stereotyping of ethnic competency.

Believing Japan is special here is part of what irks me — “of course the Japanese/Koreans do it right!” If maintaining flat-to-neutral housing prices over multiple decades in a major urban environment is your primary bugbear, you might also consider Manhattan, over the time period of 1920-1960. After the Great Depression it took ~40 years for property prices to recover!

Alas, for American writers and American readers the Great Depression is too close to home. We know why housing prices were “stable” so long. The trauma is tangible, and so we must borrow someone else’s tragedy instead to score policy points.