Or Why Tech Monopolies Are Actually Good For Society

Hold on! Stow the pitchforks! Hear me out.

Nothing lasts forever. All technologies have their moment in the spotlight — then the wheel of progress turns and a new challenger arises, one better adapted to the environment.

Progress is a cruel master. Just because a given company managed to fundamentally advance the frontier of technology doesn’t mean they’ll have a strong defense against the next challenger. The lesson of technology is the exact opposite: each society-transforming success story in Tech creates the conditions for its own replacement by funding the development of the next wave of progress…and then letting someone else execute on it, totally disrupting their monopoly.

But in the meantime, for a brief moment, we all benefit from their market dominance.

The amount of money you can make in today’s global technology market by capturing market share is absurd. It enables industries and sub-industries like Venture Capital, Journalism, and Law to thrive in its shadow. It also stirs the envy & ire of those unable to join in, inspiring a turn towards political solutions.

The goal of this essay is to show three things. Not necessarily to prove them, as that would take a book-length exploration of the technology frontier’s evolution over the ages. Just to show them in action and perhaps point some readers to reconsider both the historical record and the potential futures on offer to us. I expect these points to be counter-intuitive & unappetizing to anyone who broadly shares my background or general outlook (e.g. markets actually ~work, economics is reasonable, building things is good, progress is mandatory).

First: not only are technology monopolies “not so bad”, and not only ought company founders seek to build them, but they are in fact actively good, create massive positive externalities for the public, and are a primary source of innovation for society. When they fail, things actually deteriorate.

Second: the natural lifecycle of a technology monopoly is short — they burn bright, but briefly, which is why it’s so important that they take profits when they can. The legal monopolies we happily grant to less innovative industries with better regulatory capture (Pharma, Publishing) are far longer than tech’s natural lifecycle.

Third: the “rents” collected by technology monopolies serve two purposes. They fund the development of “toys” that later enable climbing to the next branch in our civilizational tech tree. And those rents then serve as a natural bounty payable to anyone who can commercialize those toys and help us make the leap to that next tier. No redistributive bounty could ever hope to match this natural bounty, as the former is hard-capped by productivity under today’s tech paradigm, while the latter is only capped by what’s possible in a future, more productive state.

That’s the rough pitch. “Tech Monopolies: They profit by creating positive externalities for society. They don’t last that long. And their rents are both reasonable and self-defeating.”

Progress itself depends on the natural movements of this cycle being allowed to run unchecked, despite the unease many feel when looking at these companies in isolation. I recognize that it can be hard to lose to one of these monopolies in the market. I understand the temptation to seek alternate solutions. But doing so is worse for consumers, worse for other founders, and worse for society as a whole.

These positions may be obvious to some longtime readers, but I think most readers will immediately reach for the same objections I once did! Even if you’re committed to the dismemberment of technology monopolies for other reasons, let me try to make my case…

A note for those reading this via email: you’ll need to open this essay in your web browser at some point, because your email provider will truncate the bottom ~60% of this essay. Apologies. Click here if that’s you:

A Case Study In Cascading Market Failure From Monopoly Positioning: Apple iTunes

I’ve previously mentioned how MySpace saw its revenue drop from $900m to $100m over 3 years, but in hindsight the market-altering growth of Facebook feels like a sure-thing to most people now, and consumer sentiment towards both properties is mixed at best. Debates about social media are further muddied by other factors, making them a poor case study for my thesis. So I’m leaving social media aside for a moment.

Instead, I want to talk about music.

An important caveat: I’m not an audiophile. Some of the songs on my iPhone today were recorded manually 20 years ago using one of these:

But. I do have a library of digital music I’ve collected over the years that includes a long-tail of content that you can’t find on Spotify. My attachment to that library means I still use Apple iTunes on my Windows PC to get mp3s onto my iPhone, where I then use the first party “Music” app to listen to them — the same flow you perhaps remember using back in the day before becoming one of Spotify’s 520M users.

Except one small thing has changed about this user flow: it’s now a piece of shit.

Until 2023, your only viable Windows desktop app was a buggy piece of software — a degraded version of what you used back in 2008. Few things in life are as frustrating as using legacy software maintained by a skeleton crew, whose every infrequent update makes the thing worse, laggier, and removes features.

But believe it or not, this desktop app is not the most frustrating part of the user experience of “try to listen to my personal mp3 files on my iPhone.”

No, the worst part is the first party Apple Music mobile app itself.

If you’re one of Apple’s (less impressive) 93M Music streaming service subscribers, you may not fully understand the irritation of opening your Music app on your phone to listen to some songs you bought & paid for, then having the screen hijacked by a first-party popup ad begging you to subscribe to their Spotify knockoff (complete with dark pattern button placement), except you’ve only got half a bar of service so the screen fails to load any content at all for a minute, blocking you from taking any action while it slowly loads the growth-hack.

But why is it like this?

Why is the mobile app experience worse in 2024 than in 2014?

Why is the desktop app experience worse in 2024 than in 2004?

The answer to this story may be obvious if you work in or around tech: software has development & maintenance costs! And staffing a team of developers, designers, and product managers on any piece of software is an expensive task: the cost of each developer is set by the market and is downstream of the most productive thing they could be building at that time.

Back in the 2004-2014 era, Apple was the undisputed king of content. Their iconic iPod ads dominated advertising.

The music industry was ravaged by piracy until Steve Jobs threw it a lifeline: consumers will pay for content if you make the experience seamless & price things fairly.

The iPod, iTunes store, and the later iPhone were the product of this vision, and they were monster successes. Economic juggernauts.

But something happened around 2012-2014ish.

First: smartphone penetration hit ~50% of the US.

Second: 4G came with it, bringing 12.5Mbps+ download speeds to half the country.

Third: a dark green European company took advantage of both, inflected its growth, and caused the first ever decline in Apple Music revenues!

In 2013, Apple owned 63% of the digital music market, perhaps more.

You can say many things about that. Maybe you or a business you liked was hurt by Apple’s domination. Or maybe you & your friends loved your iPods and uninstalled P2P sharing apps in favor of supporting your favorite artists by buying their music on iTunes.

What’s indisputable is that working on the software that propelled Apple to billions of Music revenue by the end of 2013 was hugely valuable for those engineers! The list of more productive things a team of devs, designers, and product people could’ve been building instead of Apple’s iTunes empire for that decade-long stretch could be counted on one hand. Maybe on three fingers.

But around 2014, everything changes. Apple sees revenue drop sharply as these new streaming technologies — made possible by Apple’s own hardware penetration & new 4G download speeds — eat its Music market share.

Their monopoly starts to crumble right as it looked strongest. This is how fast things can vanish in tech. Apple yolos $3 billion buying Beats, who had both a hardware arm and a music streaming service, the latter of which they immediately folded into a first party Apple offering. Fun fact: this was Apple’s largest acquisition to-date, by ~$2.8 billion. Panic moves money.

The result? 10 years later they aren’t even in the top 3 players by market share:

So ask yourself: at what point did staffing a large & hyper-competent product team on iTunes — for both its current maintenance and its future development — stop being the most productive thing for Apple to do?

You pick, there’s many good answers. I think by this point in the chart of Spotify’s user growth from earlier, it was already too late:

There’s a classic and tragic Innovator’s Dilemma to this whole saga.

When Apple first entered the market, there was no strategic conflict between their new user purchase model and existing legacy options. Music bought at a record store on CD and then imported into an iTunes library on a Dell PC running Windows Vista helped create a literal data moat for Apple.

Any friction in that user’s experience using Apple’s software to engage with their music would inhibit iTunes adoption and, in the endgame, reduce Apple’s revenue potential via future sales (after all the record stores get cleaned out).

Aside: you’ll note the inability to resolve a similar tension between digital & physical goods purchases massively inhibited eBook adoption.

This is wonderful from a [User-Employee-Corporation Alignment] perspective — the users using the product are happy, the business building the product profits from that happiness, and the employees working on it daily get to feel good about themselves. The “up” part of an S-curve is a super fun place to be!

But now, in 2024?

Any user not actively subscribing to Apple Music is likely using a competitive streaming service. Competitive streaming services can never have their music integrate into Apple’s first party software — the digital content sits in a walled-garden cloud server that Apple’s software can’t touch. And the revenue potential of a single song purchase pales in comparison to an endless monthly subscription.

Leasification is the ultimate endgame of almost all consumer software products.

Aside #2: note that the closed walled-garden architecture — “an App” — that prevents Apple from touching the content was explicitly created, promoted, and distributed by Apple to combat the Microsoft Open Internet strategy. They did this to themselves!

It’s not just that they’re losing market share: it’s that losing market share to a novel technology running a novel business model totally screws the RoI of investing further in Apple’s legacy product.

The new business model — Streaming — is better adapted to the environment that Apple themselves created. The only viable play in the game is to try and catch up by investing billions of dollars of capital and the human resources of your most expensive staff to try and recover.

For students of history: this rarely succeeds.

So what do you do with the legacy product while you’re trying to save the ship??

Monetization: Lots Of Fun On The Up, A Dirty Word On The Down

I linked it as “mandatory reading” in my Macroeconomics for Tech Employees essay, but whatever you think of the man, the lecture notes from Peter Thiel’s 2012 lecture on Value Systems really must be understood if you’re interested in the economics of building companies.

The key framing that’s so valuable is separating Value Creation from Value Capture.

Back to Music: when Streaming starts to eat the iTunes Empire’s lunch, the future is already written. Refer to Cassette sales or CD sales to be able to predict the future of iTunes Store music revenues:

When you have a product with an existing install base and a large-but-shrinking top-line, the playbook is pretty simple: stop investing, start extracting.

Switch to Value Capture, because the Value Creation well has run dry.

In the fun growth phase, any friction put in front of the user trying to use Apple’s iTunes software went against the company’s growth strategy. But look now:

The Digital Download format is so dead that its only hope for a comeback is 20 years from now, when Gen Z gets inspired by their own nostalgia and repopularizes the iPod nano, like millennials and later Gen X are now doing for the CD:

In the tragic decline phase, every piece of friction put in front of the user trying to use iTunes can serve a helpful purpose: extract more value from the user or redirect them to a product with higher RoI.

Instead of a balanced producer-consumer relationship, or even one in favor of the consumer, the decline phase is most aptly characterized by an adversarial relationship between consumer and producer.

Not just in the theory & strategy of it either. Sadly, employees working on a declining product are more likely to resent consumers for having “the wrong” preferences. Of course that resentment is towards the aggregate market…and yet. Their only direct touchpoint with the market is with consumers of their own product. They can’t help but look down on their own users!

And from the consumer perspective, well. Here I am, 20 years later, trying to listen to songs I’ve purchased & downloaded from Apple, blocked from doing so by a half-loaded popup trying to sell me an Apple Music subscription for $10.99/month. My Consumer:Brand relationship becomes tarnished the more exposure I have to their products — and yet I am tied to their products far more than the average Spotify-using consumer!

Nonetheless: Apple has to monetize me more in order to stay competitive. Can you blame them? I haven’t purchased a song from iTunes in a few months now, while you likely either paid Spotify $6 a month or listened to some ads for them. Software devs aren’t free.

All Media Is Alike: Eyeballs Are Zero-Sum

From a business model perspective, part of what makes Streaming successful is that it turns what was previously a one-time economic exchange into a repeated one.

It turns a purchase into a lease.

And since the total time spent listening to music per month is largely static for any given consumer, it increases the overall monetization of the user base vs. the prior one-time purchase model.

1,500 words into an essay about how the Internet died and all I’ve done is rehash the tragic death of iTunes and the ascent of Streaming business models.

But this is important because it’s one small slice of the same overall pie.

If you understand why changes in technological trends led to market pressures and incentives that forced Apple to stop investing in their core iTunes product, increase attempts to monetize existing users, and adopt growth hacks & dark patterns at odds with their prior ethos, then you’ll understand what I’m about to describe with Google as a riff on that same pattern.

This pattern is made even more painful by the zero-sum fixed market dynamics of the Media industry.

In any given year, the number of eyeballs & ears available to consume Media each month is ~static. The amount of time those eyes & ears have to spend consuming your media is also ~fixed. Thus, someone else’s success selling into this audience necessarily means your own failure.

And then on the business side of the equation — and this is the bit people often miss — the advertising dollars looking to be deployed across the entire advertising industry are roughly fixed as a percentage of aggregate corporate revenues. Every possible channel for advertising is competing for a fixed advertising budget!

If your RoI is positive but not quite as high as other channels’, your allocation will go down.

So if any part of your business model depends on individuals consuming your media OR on advertising sending you money to run ads…you are trapped in an existential zero-sum competition for eyeballs.

Good luck!

Incidentally, I described my own perspective on how best to fight existential zero-sum competitions in one of my favorite essays about Moloch. Spoiler: you’ve got to be willing to push the button.

Say A Genuine Thank You To Google: 2000-2016

My pitch is that The Internet You Loved was a product of monopoly.

For a decade and a half, we had something magical.

Now I know monopoly is a dirty word with many dirty connotations. We fear their power and cheer their busting.

Fear not, I come to bury Google, not to praise it.

The Old Internet was a free and open hub of websites linking to each other, built from an incredibly rich long-tail of content niches, forums, blogs, and media sites.

This long tail was surfaced to new potential consumers via Google search. You just searched Google using a generic hyper-object-focused version of your native language (“Google-fu”), which would return the most popular niche/forum/blog/media empire that used those words a lot.

This actually worked!

Those websites would then monetize your eyeballs by showing you ads, which they could sign up to display in a self-serve way via Google’s AdWords platform.

The viability of this ad-supported website-hosting business model then led to further supporting growth in the industry focused on making the process of getting a website up and running as frictionless as possible.

Today, in 2024, if you’re picturing someone sitting down at a desktop computer or a macbook, actually navigating to Google’s homepage, then typing in a generically-phrased search term in order to discover websites full of other users like themselves with an interest in a given niche…do I even need to mock this set up?

But back in 2005, the person doing this was young, at the vanguard of new technology, previously unreachable via legacy advertising models, and living in an era of previously unknown economic prosperity.

That is to say: they were the prime demographic to sell ads against.

Particularly this new form of simple, non-spam, non-harassing, tasteful online ads pioneered by Google:

Google did to online advertising what Apple did to purchasing online music: they made it tasteful, respectable, slick, easy, transparent, unobtrusive, minimalist, classy, etc.

The sort of aesthetic that aspiring technology-embracing, intellectually-oriented, upwardly-mobile generations prize in the post-modern era!

And the sort of aesthetic that’s only possible in a monopoly.

Google totally owned the search market.

Google Search sent traffic to any niche content site on the internet, so long as it was good.

Google indexed the entire web so they could find the very best content.

Google let all those niche content sites monetize their traffic self-serve with ads.

This ecosystem was a Garden of Eden of monetizable eyeballs explicitly birthed and nurtured by Google — they completely destroyed the “legacy” web of locked down “Portals“ with superior content, superior aesthetics, a superior user experience, and a superior business model.

It was a total rout.

In a Thielian sense, Google actually Captured a relatively modest share of the value it Created!

Google spread the Wealth they created across millions of end users! Across all of society.

They sprinkled value on users, giving them beautiful clean interfaces & unobtrusive, respectful ads with clear standards. They sprinkled value on content creators, giving them enough revenue share on a self-serve ad platform that millions could make a living by writing online. They sprinkled value on advertisers, giving them easy access to prime demographics at low cost, with never-before-seen tracking capabilities and attractive RoIs.

The result was the beautiful open web you once loved. A network of millions interacting online, creating content for each other, sitting at their desks reading away.

Were there other factors at play? Of course! Was the domination of Google itself only possible thanks to increasing internet penetration? You bet. Bill Gates’ 1998 Memo to Microsoft employees noted that his original vision of “a computer on every desk and in every home” was not yet realized, the team had more work to do.

Google was founded 2 months later and rode the wave that Microsoft paid for. (aside: again notice the thread of a Tech monopoly funding the growth of its next challenger)

You can’t just wish a global monopoly into being out of thin air. Riding trends and existing demand is par for the course. Vision, execution, timing, and luck.

I’ve written about monopoly before and the stakes involved. I’ve been explicit about the potential for conflict and abuse that it creates.

What is a monopoly, at heart, but a gratuitous surplus generating engine? When outsiders can’t Capture a slice of those surpluses in the open market, they won’t hesitate to resort to other means. And when that happens every monopolist has to answer the question: am I going to retaliate? Will I defend my profits? Am I willing to repay evil for evil?

They’ve been maligned and taxed from Asia to Europe, but you can say one thing for the Google of this era: they responded to evil with good.

And in the process, they built the Internet You Loved.

Say a ‘thank you’ for what was.

Burying Google: 2014-2024 — Attention Was All It Needed

Few monopolies last forever. Technology monopolies burn bright, but they burn briefly. You don’t need aggressive antitrust enforcement to kill them — just wait a while for the march of progress and the innovator’s dilemma to rear their heads.

The smartphone penetration and bandwidth trends that broke Apple’s monopoly over digital music came for Google too.

Video. Longform audio. Instagram. TikTok. Even YouTube.

Sure, YouTube ended up under the Google umbrella. But their model is at odds with the open internet Google created, their content is richer and better tailored for newer platforms, they compete for internal corporate resources and external ad spend…it’s all a zero sum game in the end.

Thus we get that now-familiar pressure on the core Google business model. They made billions of dollars monetizing a small slice of people’s time spent sitting at an old school PC screen, typing search queries in, browsing content.

But now that whole mode of consumption has been disrupted and coopted by other forms of media. As much as Steve Jobs hated the idea, mobile is inherently consumptive and tailored for video & audio. Today you see the TikTok/Instagram meta evolve to put captions over content so even the audio piece is optional.

The walled garden nature of Apple’s mobile platform helped insulate these competing forms of attention capture from Google’s open web. People consume app-based content beyond the reach of Google’s indexing and beyond the reach of their ad networks. Doomscrolling is the Platonic ideal of Internet Portal capture from the late 90s Venture Capitalist playbook. Everything Google fought against.[0]

Every Doomscroller enjoying the latest algorithmically concocted nugget of pure entertainment is one less reader for the open internet. One less set of eyeballs for Google to sell ads against. One less dollar to share with content creators. These upstart platforms read their Internet History books: they knew from the start they needed to roll their own ad networks in conjunction with their apps.

And the zero-sum nature of advertising budgets means these things all realign themselves very rapidly. Network effects are great on the way up, but on the way down they mean 3-1=0.

The long-tail of third parties outside of Google’s umbrella now have a less viable business model.

Google itself now has a less viable business model!

Meanwhile, market expectations are not just for stasis — the market expects you to grow.

What’s your only possible remaining play? You don’t have years to wait. You’ve got 90 days.

To quote the Apple Case Study from earlier:

When you have a product with an existing install base and a large-but-shrinking top-line, the playbook is pretty simple: stop investing, start extracting.

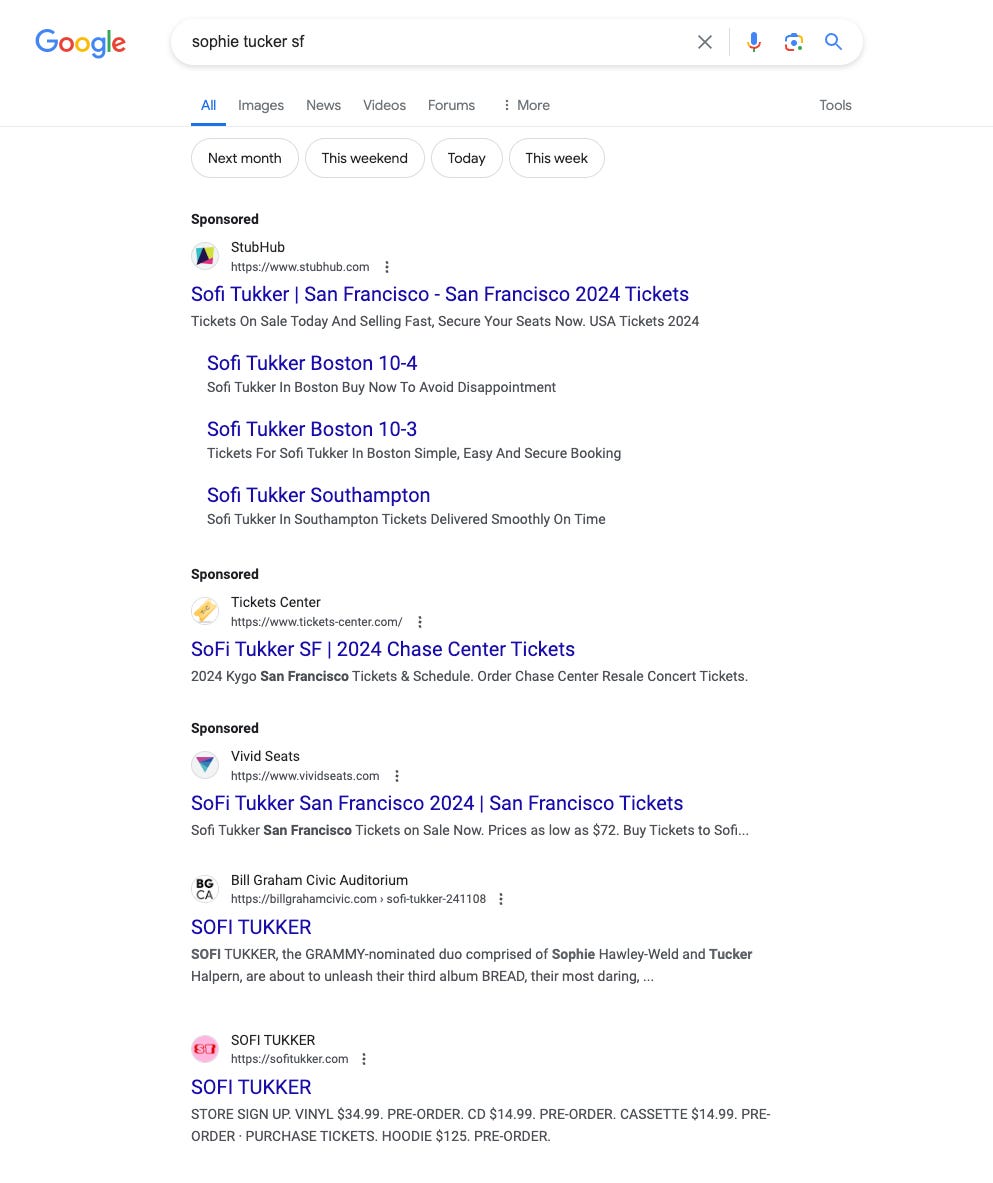

You know what was probably a pretty fun job that someone felt proud of? Figuring out how to tastefully display that small selection of sponsored links to the side of a search query and settling on the right shade of yellow background to convey “Sponsored” to the user, without denigrating the content but merely suggesting that it might also pique their interest.

You know what was probably a pretty lousy job, such that someone has to say to themselves, “hey, at least I got a lot of stock for this and can afford a house in California!” Burying an organic search result at the very bottom of a 15” MacBook Pro browser window[1].

And so Google starts slowly evaporating their own brand equity, cultivated during an era of monopoly economic power, in order to juice their revenue growth in the face of declining market share.

The Monetization of their product must increase in lock step the competition they face.

I realize most of my readers are incredibly sharp, high-verbal-scoring, critical readers and established search engine users and so will likely have no trouble discerning the “truth” of Google’s newer results — and perhaps even identifying the one true link to the hotel above that is in fact hidden in the screenshot of hotel results! However, consider that 9 years ago, when Google’s search results were clearly labeled with a yellow “Ad” tag, 39-66% of surveyed users were unable to correctly identify sponsored results:

I invite you to turn off your ad blockers and recreate this study for yourself, on your mobile browser as well as your desktop browser. Don’t ask yourself: “am I able to identify all paid-for results?” Instead ask: “has it gotten easier or harder to identify paid results over the past 9 years, since the time when 39-66% of people were unable to spot them all?”

Perhaps you already know the answer.

Economic Dissonance: Monopoly, Competition, and Innovation

The thing to note here is that the Economics 101 narrative of “monopoly = bad; exploits pricing power; produces worse consumer outcomes” has to be tortured mightily to apply to the modern Tech world.

I realize this is heretical, though it seems so strikingly obvious when you look back in hindsight.

A company that’s growing due to monopoly market positioning in a new and growing market unlocked by technological changes is…radically different from the monopolies of old. Standard Oil does have a few good lessons to teach modern companies, but the analogy doesn’t stretch very far.

Question: When was the experience of using Google’s homepage search engine the best? When was the user given the largest share of the Value created by their own presence? When was the long-tail of niche content creators rewarded with the highest rates — instead of having their content ripped and displayed to the user without any clickthrough needed?

Answer: When Google was the undisputed king of Search and Advertising, with 60%-90% market share.

There’s a tremendous irony that online gripers can be found writing repeatedly over the past decade about the sad lack of a modern analog to Bell Labs (itself obviously unsustainable once its parent company was broken up in the early 1980s) —

— meanwhile Google was incubating the researchers who created the entire modern AI industry with a paper published in 2017 and worked on from ~2014-2017:

The basic level insight of your introductory college course is that monopolies have no incentive to innovate, while competition is the progenitor of all innovation under the sun.

The empirical reality — visible to anyone who just looks at even the very recent past, let alone the ancient history of the 20th century — is that without Producer Surplus, the capital necessary to create technological innovation is unlikely to accumulate.

That goes for human capital almost more than financial capital!

Some group of people must exist who are educated, aware, motivated, and at the bleeding edge of a field…who nonetheless have some spare hours in the workweek to spend innovating on something instead of slavishly executing a task.

It’s necessary to be slightly underemployed if you are to do something significant.

Without this Slack, the system will never be free enough to innovate.

Even the first legal framework ever adopted in New England, in 1641, recognized that the grave Puritan sin of monopoly was excusable only for new technology:

One hugely valuable source of Slack is the Producer surplus that a monopoly claims for itself. Another might be the structure of modern Academia, with tenure and $50 billion tax-free endowments.

The idea that organizational-level existential competition might have negative impacts on innovation doesn’t always resonate on an emotional level with well-educated individuals, even as textbooks describe a state of idealized Perfect Competition as something out of every innovator’s worst nightmare. But the effects of even a mild increase in competition should resonate with every reader who’s experienced the painful increasing ad burden across the entire internet over the last 20 years.

And if you see how the dots all connect, you’ll understand why my title says The Internet Died, and not just Google and their vision of it.

Because these dynamics apply to every player on the Open Web that Google fostered.

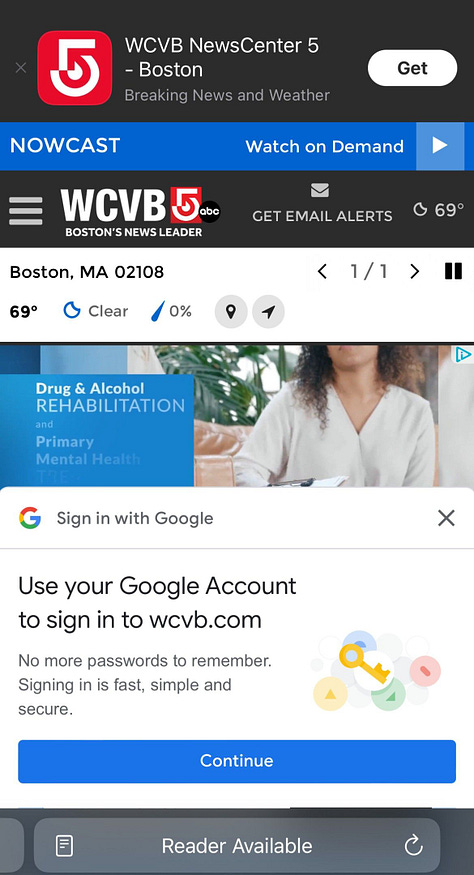

Journalism was kneecapped by the internet and instantaneous & democratized access to news. But now, as a direct result, it’s forced to make the same trade I described in the Apple Case Study: more aggressively monetize its shrinking user base in order to try and prop up revenues — actively turning what little remains of said user base hostile through dark patterns, horrific UX, spammy pop-ups, and a descent into the worst fever dreams of mid-90s web browsing.

They are begging for your attention. Yet when they get it, they must abuse it.

Enjoy this example from June, 2024. A relative told me where was a report of excessive Cyanobacteria at a lake we planned to visit. I googled it. I clicked the top link to a news outlet. This is what I got:

At the top, a banner add for a first-party walled garden app. A call to action to watch something on demand. Then a popup to give this website my Google authentication details. I ‘X’ out of that. Then another popup for my email. I ‘X’ out of that. Then beneath, a banner add that scrolls & floats!

The inflection from growth to decline as a result of competitive pressures forces the organization to adopt the universal playbook for those on the way down: stop investing, start extracting.

You can cry that they ought to try and Create some value instead of just Capturing what little they have — but they have no available Slack to do so! The competition is too fierce! Anyone who can’t justify their job today, based on net profit generated today, has already been laid off.

Incidentally, this is one reason that innovation in online content creation tends to come from the very young, significantly underemployed segment of the internet population. They’ve got Slack for days.

I’m not sure how all these online content businesses that used to be viable in Google’s empire are going to deal with the coming deluge of AI-created content, read by AI-agents. Who will pay to advertise against such low quality eyeballs? Who’s willing to bear the hosting costs? You can believe in the Dead Internet theory or not, today. On balance, I think a 2011 quote gets things about right: “it’s not the end of the world, but you can see it from here.”

The walled garden consumer attention apps may have ripped Google’s internet monopoly apart and destroyed the economics of the Old Web. But what’s left is currently still worth $2.3 trillion! The irony of AI forcing the final nail into the coffin of Google’s Internet is high. But it’s a real possibility.

Adjusted for inflation, Xerox was worth $10.2 billion when it started the PARC research lab in 1969. Today, it’s worth somewhat less. Thanks, in part, to the very technologies it created:

Videogames & Extraction: Less Money, More Monetization

Perhaps, like me, you’ve moonlighted as a gamer over the last 2 decades.

If so, you’ll have noticed the ever-increasing ratchet of Monetization creeping into every mainstream game that ships. Games are media too.

As with Apple’s products, they’re expensive to develop and there’s an opportunity cost to that expense. So now every game ships with a Battle Pass and a cosmetic cash shop. Many ship with explicit or soft pay-to-win mechanics. Many have entire game systems reworked to accommodate extra monetization mechanics. Most have content removed and then added back behind a paywall of some kind. Pay, pay, pay, pay, and pay some more. Have you considered paying?

It wasn’t always like this!

But now the competition for attention has ratcheted up. The industry has matured, massive funding flooded the space, opportunity costs have increased, dev cycles have lengthened, and your playerbase now has more compelling titles to choose from than ever before. You’re trapped in a competition with every other form of media for an ever-dwindling share of consumer attention. If you don’t milk that playerbase for all its worth, you won’t even break even. You won’t exist next year.

Once upon a time you could even rely on Moore’s law and display technology advancements to sell the next generation of games for you:

But no longer does this stuff sell more copies every year by default.

And, like iTunes, like Google Search, like Journalism…the result is the same. The product itself deteriorates in the face of increased monetization.

But the Value Capture must accelerate, because Value Creation is looking shaky. The current technology adoption wave has crested. Competition has increased. Developing markets are either plugged in already, walled off behind protectionist policies, or not yet rich enough to move the needle.

Put another way: as their global user growth stalls, Riot Games attempts to find the maximum possible price players are willing to pay for digital goods.

Why Are The Capitalists Only “Evil” When They’re Losing?

It’s interesting to ask: why didn’t these companies try to maximize their Value Capture during their heyday!?

They just left money on the table, right?

Imagine explaining this consistent pattern to someone whose only mental model of corporate decision making is “ruthlessly extractive consumer surplus minimization”. Aka “capitalists are evil”.

These companies weren’t interested in exploiting Value Capture when they had maximum market power! They only became obsessed with min-maxing it once they faced competition!

Of course, from the earnest-yet-aspiring-monopolist corporate executive’s perspective, it all makes plenty of sense. The best way to grow revenues — particularly in these zero-sum attention-driven industries — is to grow! If you’re riding a trend and have a killer product…just…keep going. A reputation for trying to screw your users will slow adoption! It’s off-brand. Didn’t you hear? Markets are global now!

Putting additional friction between you and your customers is a bad strategic decision for anyone who wants to continue serving those customers (and all their friends) for the longterm. That friction exposes you to a greater risk of technology-driven disruption and the threat of a networked unraveling of your whole monopoly.

More than that: it will likely turn off your best employees from working on your product. The best product builders for any given attention-product put themselves in the customer’s shoes. They have user empathy. They feel like trash when their paycheck involves scumming an extra $67 from an enduser who gets paid less than they do. They will create dissent in the ranks & subject your organization to unpleasant internal politicking & continual “narrative alignment” if they feel you are Capturing too much value from users they identify with!

If you’re reading this and scoffing, I promise you this is real. We can share stories over a coffee sometime. Most of the best people in Tech do not actually want to get a paycheck conning users. The easiest way to be really good at your job in technology is to care a lot about the users of your innovations.

Instead of dealing with all the misery of class conflicts & resenting your boss for staffing you with finding more ways to exploit customers: Just. Focus. On. Growth. Offer a fair deal. Leave money on the table. For users, for business partners, for third parties, for content creators.

Sometimes, Monopoly is actually good for society. Sometimes it offers the slack necessary to create healthy and productive work environments, to share Wealth with customers, to fund questionably productive investments in future technologies, and to prioritize long-term positive relationships between customers, workers, and capital.

You want a focus on short-term hyper-extractive profit-maximizing strip-mining of capital assets instead? Just subject executives to increased levels of existential competition.

I’m not saying this holds true for all industries. I’m not even saying that it always holds true in Tech.

But I am saying that you should update your mental model a bit about the unpleasant reality of what losing a competition where the cost of losing is your company’s existence, your job, your reputation, your mortgage, and your social status among your peers does to a person and their willingness to exploit other people. To their willingness to capture a larger share of the value they create, even if it makes things worse for others. To their willingness to invest in questionably productive future technologies.

What makes technology monopolies a special case is their monopoly is contingent — not on a government license or control of a scarce natural resource, but on using software, hardware, or their combination to maintain a superior market position.

Of course their market power gives them advantages over challengers — but in the tech industry those advantages come with offsetting costs. The Innovator’s Dilemma and organizational inertia mean your monopoly is always at risk if you fail to innovate yourself, if you miss the next wave, if your product quality declines, etc. etc.

Your Tech Monopoly gets to print money only so long as your customers are satisfied.

When Monopoly Fails: My Heart Is In The Coffin There With Google

Was I happier, before?

Did I love the old iTunes?

Do I miss the old Google?

Is the sorry state of journalism a shame?

Why do I even care about the decline of overmonetized underdeveloped videogames?

Am I just a corporate shill, enamoured with someone else’s profits, blind to the stifling impact of concentrated market power and inefficient monopolies?

Perhaps it’s “Yes” all round.

But what I hope to show, at least for some readers, is that some of the things we most enjoy about modern life are a direct output of people who makes things having enough concentrated market power that they don’t need to concern themselves with maximizing Value Capture.

And that the world where subjecting the people who make things to existential competition increases their level of innovation is, at best, not always the case in Tech, and at worst, a total fairy tale. Innovation is hard as shit. Squeezing some extra Value out of an over-competed market in decline is easy as pie.

Is it any wonder every corporate executive & investor looks at this crazy new AI technology and the first thing they see is a way to strip some (human) costs out of their current business?

In Tech, you can ride a wave of adoption to a massive global monopoly. And then you’re lucky if you get a decade at the top! To see the end of the second decade requires predicting & catching, or innovating & creating, a subsequent technology wave.

In Pharma, we grant 20 year patents to whoever innovates a drug. That’s a legally protected guaranteed monopoly to encourage innovation. In media, we grant 95-150 year monopolies.

Tech doesn’t need any of that. Patents are not particularly useful for innovation unless you want to leak your strats to everyone else — and the international competitors will just copy-paste your products regardless of IP protections and then sell them into the global market. The natural monopoly of building & spreading a new form of technology is its own monopolistic reward. And that natural monopoly has a natural lifecycle today of a mere 5-15 years!

A beta reader advised me that I ought to harp one more time on how Google funded the development of modern AI…but entirely failed to capitalize on their own innovations until every individual involved had left and started a company based on their work at Google. This is not an unusual outcome in Tech.

These things will die. Open will replace closed. Closed will replace open. The Bazaar will destabilize the Cathedral. The Cathedral will consolidate the Bazaar. Technologies will be bundled and unbundled.

From an outcome-maximizing perspective, you don’t need to bust these companies up or slow them down or tax them more or subsidize competition or do any of that crap. This isn’t an oil field. It isn’t a drug that cures obesity. It’s just innovation.

Technology Thrives on the Interplay of Moloch and Slack

Of course, I understand that the motivating rationale for supporting antitrust action against Tech is often at least partially driven by things beyond pure economic considerations.

Often reflexive anti-Tech sentiment involves some combination of:

A personal career that’s been disrupted by Tech or a feeling that the boat has been missed

Experience with or distaste for the higher-order effects on society of concentrated market power in the hands of a few highly-regionalized culturally-homogenous marshmallow-test-acing elites

In democracies all over the world, this involves accusations of undue election interference one way or another

In autocracies, it involves accusations of going against the national interest

Feeling like you live beyond the economic reach of Tech’s influence such that the gravity well of productivity & profits doesn’t reach you, and you are instead just another source of monetization and future growth for an entity that won’t ever benefit you or your community

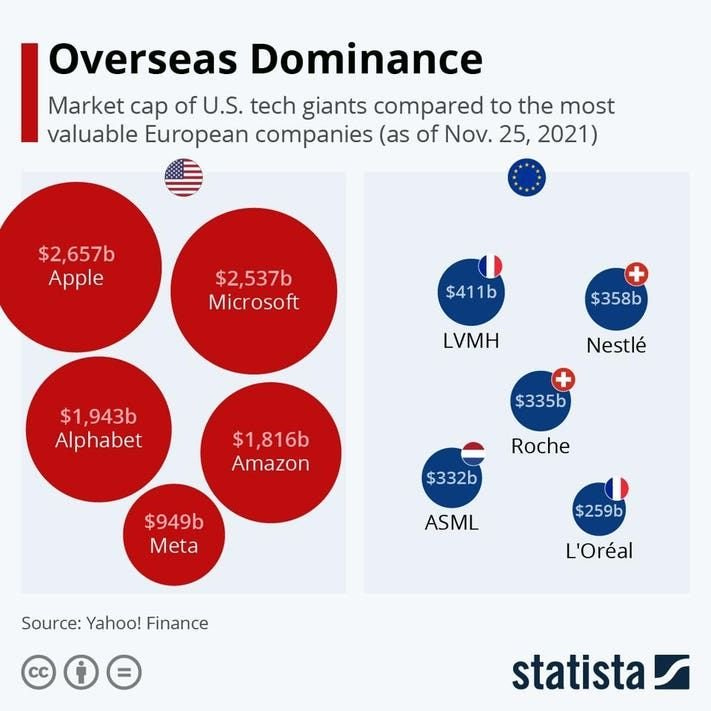

Read the Industrialism section of my Full Stack of Society: Can You Make A Whole Society Wealthier? magnum opus for more — ctrl-f for “You ever wonder why the EU gets so mad at Google & friends?”

Rarely, but occasionally, noting that domestic tech companies benefit from outsourced global manufacturing operations such that the Wealth they create for domestic citizens is limited only to the upper-decile of test-scorers, while the traditional base of domestic “labor” is viewed purely as a revenue source and has no means of interfacing with the chain of production

Even “influencer” roles — traditionally more open to people below the top-decile of white collar work — reflect this same divide, merely allowing one influencer to adopt the same half-symbiotic half-parasitic relationship to their followers as tech does more broadly to the domestic population

I’m open to others. These are varying degrees of reasonable and understandable. It may surprise people who’ve only been reading this essay at a surface level, but if I could wave a magic wand and cause the dissolution or disruption of at least some large Tech companies with extreme market power, I probably would.

But I find the reflexive condemnation of these businesses purely on the grounds of simplistic classical economics models and market power to be inappropriate — and especially unbecoming from people who work in the industry!

I am not advocating an eternal monopoly of Big Tech corporate overlords. The explicit point of my case studies is that the money made by technology monopolies, coupled with the natural progress of new technologies, puts a natural end date on these things.

Mine is an optimistic worldview!

If you don’t believe technological progress is possible, you should discard my views here and just try to Capture as much of the Wealth as you can from today’s tech monopolies, secure in your belief that doing so will have no higher order effects on future innovation.

I understand why this view comes naturally to bureaucrats and European lawyers.

But know that those who want to legislate a technology monopoly away are merely reducing the size of the prize for future innovation. Mentally modeling these higher order impacts may be counterintuitive for most, but I want more people involved in the business of innovation to be willing to defend it.

The naïve anti-monopolist views the existence of a tech monopoly at any point in time as a market failure. I view the existence of those businesses as a spark in the dark, necessary to fuel the fire of progress. Not only do I believe tech monopolies naturally decay — the executives at these companies believe it too! That is the animating force behind the continual attempt to expand the surface area of their platforms![2]

The ones who make it through multiple decades only do so via continual innovation. You can’t just extract value forever in the tech industry. But the most controversial part of this worldview is realizing that their continual innovation is funded, in part, by the excessive human & financial capital surplus their monopoly enables.

As painful as it is to confront, as much as we wish it weren’t true, innovation can in fact be crushed by competition. Productive output can be crushed by competition. Consumer surplus can be crushed by competition.

Everything you know and love. Can be crushed. By competition.

Even the Internet.

The Internet I loved is gone. My son will never know anything like it. But perhaps he’ll get something new and magical in its own way. And I hope he gets to see the wheel turn again, if only to learn the lesson as I learned it.

But the Internet is dead.

Long live the Internet.

Notes

[0] The locked down walled garden incumbent is undone by the free and open challenger. The free and open incumbent is undone by the locked down walled garden. The wheel turns, the cycle completes. $5 for where the next cycle is going. See you there in 20 years.

[1] Or this example from a friend that puts a scammy site above the actual venue — hey man, it’s all dollars to Google!

Scam site supporting evidence — the top BBB Complaint referencing Google’s Search Results sending them to this scam site first is the icing on the cake.

I of course am aware of how Google’s evolution is itself also partly a result of a battle between its own technology and those who try to manipulate that technology via SEO dark patterns. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Google’s conflict with startup RapGenius escalated to a new level of ferocity in exactly 2013 — a timeline that lines up very well with some of the other trends discussed in this essay. For their visible misbehavior, RapGenius was martyred by Google, completely removed from Search results, destroying their only form of user acquisition.

It was a massive and one-sided escalation. The kind you only see from a ruler who feels its grip on power slipping.

[2]

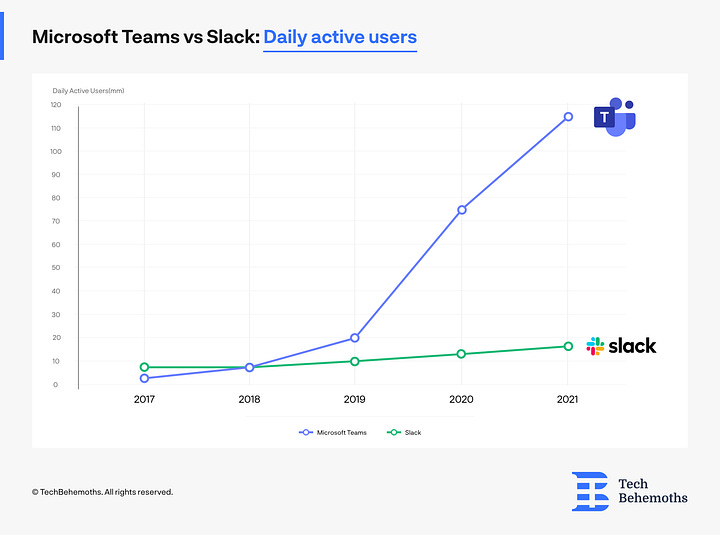

“Microsoft was inspired to develop new software because of Slack’s success, and now that they’ve got a product that’s market-viable they’re bundling it with their existing product suite, making Slack’s business model harder!”

Yes, that is exactly what competition looks like. Competition is not “chums sit around and agree to share the market with each other.” Competition is “we try to put each other out of business.”

Anything else is called a Cartel.

There’s an instinct here to defend Microsoft’s pricing practice by appealing to Consumer Surplus — which is greater in Microsoft’s domain than Slack’s. But let’s be clear: Slack built a $30b business by innovating, unbundling, and exploiting inefficiencies in Big Tech product development. They burned bright! They had market share dominance!

And they got paid $30b for that.

Then they lost because their distribution model was not as effective as Microsoft’s, much as Spotify crushed Apple’s “legacy” music business, and much as Apple crushed the CD industry’s before it.

How it started vs. how it’s going:

I think Salesforce is an insanely awesome $250b business with incredible technological & social lock-in on its core CRM product and natural adjacencies with many other Go-To-Market related business tools. I can only hope to be lucky enough to build something a fraction as awesome.

But Salesforce bought Slack on July 21st, 2021.

Exactly one year later, they announced the first ever increase in pricing for Slack — “to reflect all of that added value and ensure that we can keep investing in innovation”.

This is not a complex playbook. Monetization must increase to offset the declining growth expectations. Reminder that Microsoft Teams overtook Slack in 2019.

Microsoft might have been late to the game, but their ability to put a substitute product into the market at a lower marginal price is the exact deflationary pressure that technology is meant to create.

They did not owe Slack market share. They have the ability to offer customers more for less — and doing so aligns with their core business strategy. They are willing to “push the button”, as I put it, again and again and again. Until the next wave of technology comes along, and then they’ll invest in that with a 100x bet. And then they’ll keep “pushing the button”. This, it turns out, creates immense positive externalities for society.

The reflexive argument against Microsoft is simply that their pricing strategy makes it harder for other businesses to compete. This argument can be made very persuasively! But it entirely hinges on the listener conceding to a worldview that competition is intrinsically good and increasing it is always net-net good for the aggregate market.

That worldview is taught extensively in schools. You can assume most smart people will concede to it. I used to use it when arguing with others. But those who know better ought to be able to engage rationally and fairly with the ultimate claim: what creates the best outcomes in terms of the intersection of product quality and price?

IF Microsoft then throws their whole strategy out the window and starts trying to exploitatively ValueCaptureMaxx from their customers like a cartoonish Robber Baron of old, your first assumption should be that their growth has stalled and they don’t have a playbook to reinvigorate it.

Your second assumption should be that they will be creating the circumstances that enable an upstart competitor to come after their business.

Maybe they do get to Capture some excess profits in the short-term! But technology monopolies don’t last forever. The stakes are just too big, the entry costs too low. The worse they behave, the easier it will be to challenge them.

Note for regular readers: I do think there is nuanced ground for critique here, which is that the technology landscape, when left unfettered, will tend towards the creation of large centralized platforms. Which means that if you want to compete against Microsoft, you can’t JUST compete with their Teams product. You must inevitably aim to compete with the entire company. Which increases the capital burden of making a challenge in a way that rewards Microsoft shareholders more than startup challenger shareholders.

As noted earlier — TikTok and Instagram roll their own Ad networks, a highly complex product on its own merits.

Thankfully it turns out that there are massive pools of capital chasing returns in a relatively low-innovation background environment, and even under our current interest rate environment startups are able to raise massive sums of money to pursue their platform growth ambitions.

Ultimately, I still think this is a fair & reasonable equilibrium, whose net outcomes are massively positive for society as a whole. Hamstringing a business providing a better adapted product at lower cost to the market based on a hypothetical of what it might do does not help innovation — it just locks in a duopoly and lowers the value of future disruption.

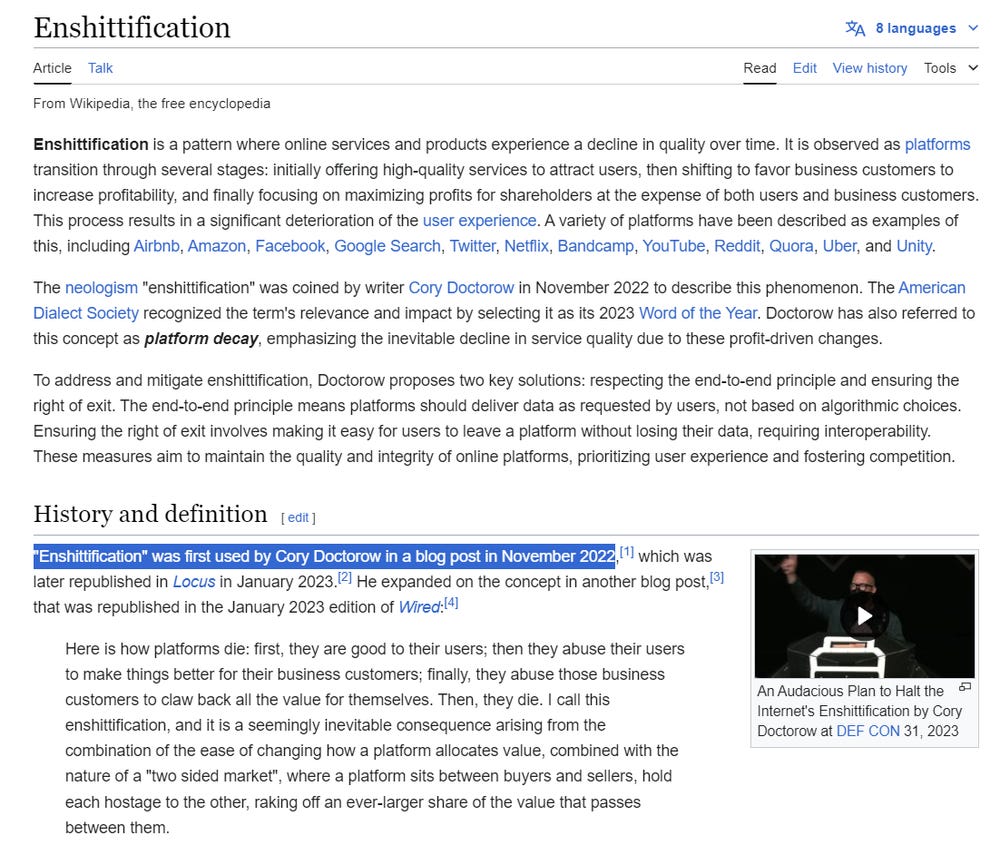

[99] I have NO IDEA how Cory Doctorow managed to get credited with creating the vulgar & overly conjugated “enshittification” in 2022 when WIRED’s Robert Capps wrote a terrific piece 15 years earlier (!) exploring the inevitable “crapification” of everything and explaining that you better get used to it, because it was going to get a lot worse (spoiler: it did).

The WIRED article is particularly amusing given the way it describes the MP3 product upending the CD market.

I read this article at the time. I thought it prescient.

I did not predict what Streaming would then do to the MP3 market.

But what I like most about this WIRED article is that it understands the bleak view.

Eternal September is coming for us all.

To some, it looks like the crapification of everything. But it’s really an improvement. And businesses need to get used to it, because the Good Enough revolution has only just begun.

[999] Burying this thought down here where it belongs. Perhaps I’ll explore it more later. But if you read my two-part Book Review of the 1517 historical analysis, Discourses on Livy, you’ll have encountered the idea that “A Chief Executive’s Only Path To Safety Is Through The Masses” —

which is to say that the best security a centralized, individualized power has is to ally itself with the masses and secure their wants and needs.

My analysis contrasts this view to modern corporate power dynamics at the individual level.

But I think you can also squint a bit and move up a level.

In the same way that an Emperor’s best protection from conspiring elites who would stab him in the back to increase their own power is to ally himself with the people and secure their needs…

…a Monopoly’s best protection from conspiring elites who would stab it in the back to increase their own wealth is to ally itself with its broader customer base and secure their prosperity.

Under this framework, a Monopoly derelicts its duty when its switches to an adversarial, extractive relationship with its current and potential customers. In that scenario, it is no longer worthy of its own monopoly and fair game for other elites. The question then becomes: does the natural market environment allow other elites to Brutus a monopoly who has switched into an overly extractive relationship with the people?

If not, perhaps the elites who try to drag it down can actually be defended. Once they succeed, how do they act? Do they restore a positive value-sharing relationship with the people? Or are they merely satisfied with their own fat slice of pie? The answer to that will tell you much.

If yes, if the market naturally affords counter-elites an opportunity to destabilize a monopoly and capture its surplus generating customers, then elites who pursue that cause of action should also be lauded! But at the same time, those who seek political solutions against the offending monopoly should be seen not as allies, but as opponents of progress. They are reducing the size of the prize, increasing the organizational costs of doing business, and ultimately attempting to enforce cartelization, whether they realize it or not.

You cannot champion progress by fighting its enemies with the tools of anti-progress.

Lmao I did a project for a freshman econ class on Riot's price discrimination, talking about how cool it was that the game was funded by enthusiasts and free for everyone else. That was peak NA hype, between 2016 MSI - 2017 Worlds, and right before Prestige Skins. I don't know if Riot monetized NA players more than China's players, but it seems safe to assume so. The last thing I saw re: League was that TSM couldn't drop the FTX from their Twitter handle, and now this skin... you hate to see it.

Well this was a ride, thanks for writing it. It is difficult to come up with models that will work across the majority of cases, so I appreciate what you have come up with here.

And I wonder if it isn't a monopoly that is valuable, or the platform they tend to create to become a monopoly.

In the example you gave of Microsoft's monopoly + slack allowing the internet and web 2.0. I think if Netscape would have won—or just not have died—we would have gotten the web 2.0 much sooner, and not as some technical wizardry of getting javascript and XmlHttpRequest to walk on their hind legs, but an actual designed platform for applications on the web. The whole time Microsoft was neglecting their browser once they had their monopoly and Netscape was out of the picture.

And in the IBM example on your chart, the only thing IBM lended to the PC industry, was their BIOS—which is not high technology. And yet, that was everything because it lended a platform that made the PC industry valuable—programs could be exchanged across different vendors.

We should be supporting platform monopolies, these allow many other players to capture value, and it becomes in their interest to strengthen the platform.

The Spotify example is a good one though, and I don't know if I would call that a better platform for musicians than Apple Music? I guess because the record labels got some equity?